Damien Leloup was one of the youngest and last crewmembers to sail aboard Jacques Cousteau’s iconic vessel Calypso.

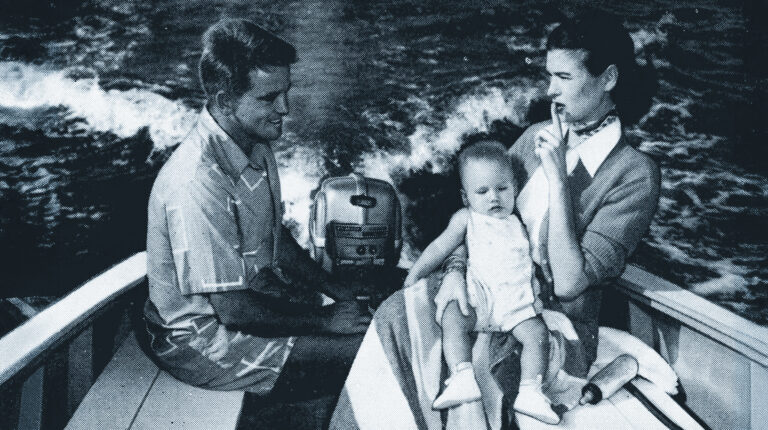

A forgery, a train ticket and an address. The childhood dreams of Damien Leloup hung in the balance as he awoke in his parents’ home in the town of Montcourt-Fromonville, France. The forged sick note would get him out of school. The train ticket would get him to Paris. And the address would get him to the doorstep of the world’s most famous ocean explorer, Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

Leloup was just 17 when he boarded the train, old enough to find his way in the city but too young to realize his plan was a brash one. “The day before, I went to school expecting a good grade that turned out to be terrible. Everyone was making fun of me. My parents were yelling at me, because my two brothers had snitched on me before I even got home. That night, I switched on the TV and my eyes opened wide. I saw Jacques Cousteau in an inflatable boat with a red cap on, and I knew that was what I wanted to do.”

At the end of the program, Leloup jotted down the address for the Jacques Cousteau Society—233 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris.

“Hello, I would like to see Jacques Cousteau,” said the runaway teen, as a secretary carefully looked over the boy standing before her. She tilted her head from side to side before deciding to let him in. Cousteau, she knew, had a soft spot for youth. Had Leloup been 30, he might have never crossed the threshold. But today was his lucky day. Cousteau agreed to see him. A few steps later, Leloup was star struck as he entered the office of his hero. “He was sitting at his desk,” Leloup recalls. “It was shaped like an L and made out of glass with books and papers on it. He was writing, most likely on his next show. I introduced myself and said, ‘Captain. I would like to work for you.’”

Inching towards his 80th birthday, the explorer eyed his ambitious young recruit and asked to meet with him the following day over breakfast. There, amidst buttered baguettes dipped in coffee at a Parisian cafe, the two made an informal deal: Leloup would return to school and study skills that would be helpful on an expedition: the basics of biology, diving, underwater archaeology and a few new languages. In the meantime, he could volunteer at the Cousteau Society.

“When you are 17, you think anything is possible,” Leloup says.

Before arriving there, Leloup’s seafaring experience was limited to a makeshift raft created out of plastic bottles that he paddled around on a lake behind his family home. He would search for crayfish and hedgehogs day and night, reveling in the fairy-tale freedom that an old-growth forest provided.

By the time Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was dominating MTV’s playlist in the early 1990s, Leloup entered his third year volunteering for the Cousteau Society. One year removed from his teenage years, Leloup says he was stunned when he received a call from the same secretary who had opened the door for him. “She said they had a space on board Calypso in Vietnam and asked if I would like to join.”

The meeting played out like a novel. Leloup touched down in

Saigon for a rendezvous with the ship’s captain, Commandant Alain Traonouïl. Together, the duo sped towards a harbor on the Mekong River in a tuk-tuk, duffel bags in tow. “The tuk-tuk dropped us in front of a building, and Calypso was behind it. All I could see was the steel superstructure used to look for whales and icebergs. It was one of those moments you dream about for years, and you think it is never going to happen. But it did. I could not take my eyes off of that superstructure until we walked around the building and I saw Calypso.”

Leloup climbed the gangplank and jumped into his childhood dream. He made a beeline for the observation bubble, a dome beneath the waterline on the ship’s bow that allowed crewmembers to observe sealife beneath the waves. He ran to the galley, where a cook was busy slicing and dicing an array of colorful Vietnamese vegetables and spices. And he mingled with the skeleton crew of a half dozen preparing France’s most famous ship for a port call to meet up with the rest of her crew in Singapore.

As her twin, eight-cylinder General Motors diesels burbled to life, Leloup realized how far he had come from his homemade raft in the forest. The ship beneath him was nearly 140 feet long. Built out of Oregon pine in 1941, Calypso served as a minesweeper in the Royal Navy during World War II. Afterwards, she was used as a Maltese ferry until a new odyssey commanded her fate thanks to a British business mogul named Loel Guinness, whose older brother ran a well-known brewery in Dublin. In 1950, Guinness purchased the ferry, refitted her and leased her to a young French oceanographer for the symbolic sum of one franc per year.

Thus began a career of exploration that saw her sail the seven seas with a starring role in footage that would earn three Oscars, a fistful of Emmy awards and top honors at the Cannes Film Festival. Her decks launched divers, filmmakers and researchers in every ocean clad in their signature silver dive suits below the surface and red beanies above. Her bunks held 27 crew members situated on three decks that also harbored photography and science labs, a helipad, a hydraulic crane and storage for a miniature submarine. The old warship hardly resembled her military days and was going strong in 1994 when Leloup lucked into a berth.

“I was immediately used as the person doing everything that the rest of the crew didn’t want to do,” Leloup says. “I was getting food for the cook. I was hopping in a Zodiac and painting the ship. I was hauling camera equipment for the film crew. And that was fine with me. Today, it would be like volunteering for Elon Musk to go into space. You’re going to do everything he asks because you are so happy to be there.”

Odd jobs on Calypso ranged from cleaning the inside of the observation bubble to paint work to, in one case, acting as an impromptu exterminator to remove a family of rats that made camp inside the ship’s submarine. The small sub, named SP350, was capable of descending to 1,100 feet when it wasn’t being ransacked by rodents. “They had eaten all of the cables,” adds Leloup. “I was crawling around inside with a torch light, trying to make sure all of the rats were gone. The only way to do that was to put a bit of food in the sub and see if it disappeared. Once the food stopped disappearing, the rats were gone.”

The majority of Cousteau’s crew outranked Leloup by 20 years. They were veterans of expeditions to Antarctica and the Amazon, award winners and salty dogs whose misadventures in port were nearly as impressive as their silver screen productions. Leloup recalls a breakneck run for baked goods in South Africa that would put Tom Cruise to shame.

“Cousteau had been using a yellow bubble helicopter named Felix since at least the 1970s. It was a two-person helicopter that we often kept on Calypso, and its pilot was a crazy man,” he says. “One morning, we were filming from a Zodiac off the coast of Cape Town. The pilot landed on a beach beside the Zodiac and picked me up. Then, we flew around Table Mountain to a parking lot next to a boulangerie, landing right in the middle of the parking lot. We ran in, picked up several bags full of croissants and headed back to the crew.”

On another occasion, a personal fax from Cousteau himself sent Leloup on a nauseating mission that affects him to this day. It read simply: “Send Leloup to pick up the blood.”

The blood was for great white sharks, which are prolific in the waters surrounding the Cape of Good Hope. But thanks to swirling currents and silt, the sea picks up a murky tint that makes filming under the surface a challenge. That meant footage of South African great whites needed to be gathered on the water’s surface; for that, Cousteau’s crew would need chum. “The next morning, they sent me to pick up the blood. I thought it would be like getting a bucket and coming back. But they sent me to a slaughterhouse, draped me in a raincoat with yellow boots and handed me an empty bucket.” Leloup laid beneath a slaughtered cow as its blood filled the container to the rim.

“I didn’t eat meat for six or seven months,” he said.

For four years, Leloup worked alongside Cousteau’s foundations and film crews, alternating between stints on Calypso and her modern fleet mate, Alcyone, a 103-foot, double-masted turbo-sail with a 29-foot beam launched in 1985.

Leloup worked his way up from sea gopher to a logistics manager and was assigned to Cousteau’s personal stateroom on Alcyone for a time. Often, this work required wake-up calls in the pre-dawn hours with dive times set before sunrise. Sometimes, it involved land expeditions into the lion-filled plains of Kruger National Park. During each trip, Leloup would find his mind slipping back to the day he boarded a train with a forged note and youthful determination in his eyes.

“I still remember the strawberry jam on his baguette,” Leloup says. “I remember the name of the café, La Mascotte. And I remember that for two hours, he gave his time to a boy to talk about his future. That’s the kind of person he was.”

According to Leloup, Cousteau was a unique leader: “Jacques Cousteau was the only leader I have ever known who asked everyone’s opinion before he decided something. Even me, a 20-something kid who didn’t know anything compared to the people around me. He would ask what my thoughts were on a subject. He was an extraordinary example in leadership.”

Cousteau was fiercely focused on helping the ocean. He wanted to give people an emotional connection to the sea and its wildlife, and he had a respect for people from every political background. “He tried to unify the world,” Leloup says. “People believed in him because they had a deep respect for the man.”

By 1995, Calypso was in a Singapore dry dock undergoing maintenance as her crew climbed aboard Alcyone and made for the great lobster migration off the coast of Africa. There, Leloup’s world came full circle as Cousteau’s respect for the ocean merged with the memory of a young boy who had collected crayfish in Montcourt-Fromonville, marveling at the animal’s intricate anatomy and mysterious movements. As Leloup descended into the currents colliding between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, he spied a train of lobster that seemed to stretch for miles.

“They were all touching their antennae to the tail of the lobster in front of them,” he says. “They were migrating, mating and enjoying one another. I will never forget that moment because there I was, in Cousteau’s silver dive suit, watching these giant crayfish following each other in line to a destination only they knew. It was so touching, so moving.”

Months after the great lobster migration, the weathered warship that sparked Leloup’s dreams met disaster. In January of 1996, a barge accidentally rammed into her hull and sank Calypso while in port in Singapore. News of her sinking would have been a national headline in France, but the passing of former French President François Mitterrand on the same day meant that many people did not hear about Calypso for weeks.

Thanks to an unusual twist of fate, the most famous science vessel in the world lay submerged for eight days largely unknown to the people of her home nation. She was eventually raised only to suffer extensive fire damage in 2017 and has been embroiled in legal battles while awaiting repairs. As recently as 2016, the Cousteau Society planned to return Calypso to service with new engines.

As for Leloup, his time with the Cousteau organization was cut short at nearly the same time Calypso sank. Forced into compulsory service for the French military the same year, Leloup was shipped off to an island in the Indian Ocean. Jacques-Yves Cousteau died just over a year later, on June 25, 1997 at age 87. Today, Damien Leloup carries on the legacy of the historic explorer as an archaeologist circumnavigating the Pacific Rim in search of answers to the climate-change puzzle.