A specialist in marine catastrophe, Sylvia Tervoort is also into half marathons, art and savoring the occasional Chicken McNugget.

Prefer to listen? Listen to this article in the player below:

Sylvia Tervoort does not appear to be a salty, globe-trotting, tough-as-nails phenom. There’s no sunburned visage, no vast distances in the eyes, no marinized baseball cap. Indeed, when I first caught sight of her last December in the parking lot of the Glynn Avenue McDonald’s in Brunswick, Georgia, I was slightly mystified. She was certainly a bit younger than I’d expected, but otherwise, although she’s Dutch and hails from a town just north of Amsterdam, she looked like your average American tourist—maybe a casually dressed professor or lawyer—hitting Mickey D’s for a quick bite before cranking up a pre-Christmas shopping spree amid the burgs and marshlands of Georgia’s Golden Isles.

But Sylvia was no tourist—not by a long shot. She was, instead, a Smit salvage master, an exceptionally rare breed of cat whose chosen milieu is maritime catastrophe—big, fat, radically expensive, radically complicated, radically high-profile and occasionally life-threatening maritime catastrophe. But even more intriguing, she was at the time the only woman in the entire world doing such an extraordinary job. And she’d been hard at it in southern Georgia for approximately four months now, leading the charge on a huge, multifaceted project—the safe, environmentally responsible salvage of the M/V Golden Ray, a 660-foot Korean car carrier that had inexplicably capsized in nearby St. Simons Sound with 23 crew members, 4,200 Kia and Hyundai automobiles and 320,000 gallons of fuel oil on board.

She waited for me beside her little white rental car, smiling, with blondish hair, maybe a freckle or two, dressed in pink corduroy bell bottoms, running shoes, a lime-colored blouse and, in keeping with the briskness that often characterizes the sunny South’s winter season, a loose black sweater jacket.

“Hello, Bill,” she said, slamming her car’s door.

“Finally, we meet in person,” I replied as we shook hands and proceeded towards the restaurant.

During several phone calls over previous days, we’d agreed to get together at the McDonald’s on Glynn Avenue because it was a landmark of sorts in Brunswick, a small town with few establishments where a couple of people could sit down, have a cup of joe and palaver to their hearts’ content. As I held the door open, Sylvia explained that she was finally shutting her salvage offices down.She’d be headed back home to the Netherlands on the morrow, along with what remained of her salvage team, a highly-specialized group of roughly 50 individuals, both American and Dutch, with expertise in such varied disciplines as naval architecture, deep-sea diving, rigging, computer-simulation, tug-and-barge handling, oil-recovery, crane-operation, welding, chemical analysis and structural engineering.

“Yes, our job is finished,” she said. “There was some little spillage, that is true, but now all of the oil is safely removed. It will be the work of another company to deal with the remains of the ship itself. And I would say the handoff has gone quite well.”

Sylvia seemed both pleased and relieved by this. Protecting the sandy, verdant shores of St. Simons Sound from a slurry of fuel oil, antifreeze and motor oil, as well as chemicals and other pollutants, was no longer her responsibility. We stepped up to the counter and ordered. Tea for Sylvia and black coffee for me.

“And I would also like some Chicken McNuggets,” added Sylvia, with a certain flair. “It’s my guilty pleasure. For many, many years, Chicken McNuggets is the only thing I will buy at a fast-food restaurant. Otherwise, it’s no fast food for me.”

I figured I knew a good bit about Sylvia at this stage of the game. I knew she enjoyed taking university courses in Holland when she was not working, her most abiding interests being art and literature, subjects she feels give context to today’s events. I also knew she was seriously committed to exercise and more particularly running half-marathons and 12Ks when there was time. And I also knew (or was willing to bet) she was probably the most macho, crisis-tested, internationally traveled and linguistically talented human being ever to dine within the four walls of this particular burger-flippin’ restaurant.

But the McNuggets thing? It’d taken me by surprise, actually. And I must admit—it had also struck me as endearingly down-to-earth, even humble, given the role I knew Sylvia had played in the life-and-death struggle that had arisen shortly after the Golden Ray’s capsizing. I watched her being interviewed on national and cable TV in the midst of the crisis. She’d always seemed steady, knowledgeable and forthright—the real McCoy.

The saga of the Golden Ray began around 2 a.m. on the 8th of September last year with an emergency call to the U.S. Coast Guard. The car-carrier had just toppled over in St. Simons Sound and was now laying on her side in approximately 30 feet of water. She’d apparently lost transverse stability while making a turn at Jekyll Point shortly after departing the Port of Brunswick, first listing heavily to starboard and then rolling back to port. While the pilot on board had reportedly the presence of mind to swing the ship out of the main shipping channel into the shallows before she’d gone over, the ship’s crew remained trapped on board under dire circumstances. Fire had broken out with dense smoke. Electrical power was gone.

The Coast Guard responded immediately. Two helicopters with rescue swimmers were dispatched, and within a few hours everyone had been airlifted to safety except for four unfortunate souls. These guys were all engineers, presumed to be somewhere well belowdecks, probably in or around the ship’s blacked-out, partially flooded engine room. Authorities also presumed that the men were (or soon would be) enduring life-threatening conditions, fraught with noxious fumes and very high temperatures.

Stakeholders began conferencing. Calls came in from family members, media outlets and local citizens. And shortly after dawn, the South Korean owner of the ship (Hyundai Glovis) and representatives of the Coast Guard, as well as local, state and federal authorities, all agreed: Donjon-Smit, a Dutch-American joint-venture salvage company with a world-wide reputation for successfully and rapidly dealing with maritime disasters, was the answer.

“What happened next,” said Sylvia, her eyes momentarily obscured by the steam arising from a cup of Orange Pekoe, “is what always happens. It is the story of my life, really. First comes a call from my boss. I say some hurried goodbyes and no, I don’t know when I will be coming back. Then there is the last-minute check of the large, heavy case that I typically carry in the trunk of my car. Is everything there? Personal protective equipment? Life jacket? Helmet? Gloves? Gas meter? Overalls? Boots? And then finally, there is the rush to the airport.”

The rescue that ensued was textbook. Once she’d arrived in Brunswick, it took little more than a day for Sylvia and her international crew of salvors to locate and extract the four desperate engineers from the Golden Ray’s sweltering hot, toxic interior. Alerted to the location of the four by a faint tapping from within the ship, the salvors began by using a non-sparking, explosion-proof drill bit to bore a small hole near the stern so they could lower a gas meter to assess breathability. Then they enlarged the hole, again using the proper non-sparking, explosion-proof tools, lowered food and water to the engineers, enlarged the hole again and finally entered the ship’s interior themselves to locate and guide the men to safety. While multitasking logistics and communications with the team on board during the process, Sylvia had also liaised with the Coast Guard, the ship owner, family members, national and local media and other concerned parties ashore.

“It was not so easy a thing to do,” Sylvia explained. “Our team was, of course, not familiar with the interior of the ship. And it was difficult for them to familiarize themselves in a place that was completely dark and at a 90-degree angle to what it would otherwise have been. And it was also difficult because the space was partially flooded, slippery with oil and the atmosphere was doubtful, due to smoke and oil fumes. Plus, it was hot. I think it was something like 160 degrees Fahrenheit in the ship at that time.”

“Sounds really dangerous to me,” I suggested. “You must have felt very good when the rescue was complete?”

“Yes, very good and very proud of those who actually did the work,” said Sylvia. “But I do not like to say things are dangerous, really. I prefer to think of these things as risk—you calculate the risk and then you do what is possible to minimize the risk. Not a single member of our team was hurt during the operation, in spite of the conditions. So, everyone is going back to their respective homes the same way they arrived—in good health. And, we saved four lives. Yes, I felt, like you say, very good when the rescue was complete.”

I asked Sylvia to tell me how she’d gotten into the salvage business in the first place. Coincidentally enough, I’d once thought about getting into it myself, I told her, back in the day, when I was running oilfield boats in the Gulf of Mexico and occasionally sharing big, semi-submersible-related jobs with giant Smit Salvage tugs—fast, high-powered, wonderfully romantic and attractive vessels. Veritable wolves of the sea.

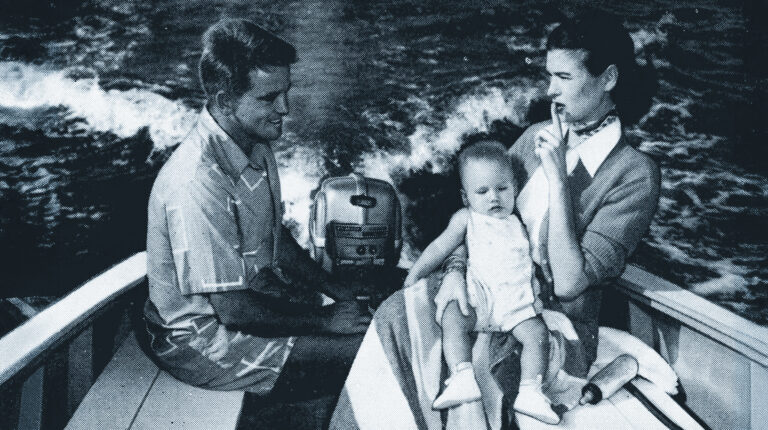

“Well,” she said, “I suppose the way I ended up with Smit is a little bit interesting. You know how it is—coincidences often make your life. The people you meet and the friendships you build. So anyhow, it’s strange but I have nobody in my family who has ever had any marine connection, any connection to the sea. And I think my decision to go to nautical college when I was young—it was either that or nursing school—was shocking to my parents. When I was finishing up my apprenticeship, I was sailing on a Dutch chemical tanker owned by a Norwegian company and, during my last days of apprenticeship, I told my parents if you want to see what I am getting myself into, you should come to Norway and visit my ship. So, they did.”

“And were they favorably impressed?” I asked with a smile.

She paused, smiled broadly back and said, “Oh, yes, yeah. It’s a different world isn’t it, these modern ships. And I think my parents were very impressed. And I continued working for six or seven years for that same Norwegian company—Jo Tankers—but then one of my friends, a fellow student from nautical college, told me about a position available at Smit, a very old and respected Dutch company. So I came to Smit and, at first, my work was safety- and policy-related and I didn’t like it. I was working in mostly an advisory capacity, and eventually I began thinking that, to make a real difference in the world, you have to be in the field. And about this same time, I came into contact with some salvage jobs at Smit, and I decided I liked salvage very much because it was so operational, and I got to make my own decisions on how to improve things. So yeah, I switched.”

Like most professional seafarers I’ve known who thrive on risky, high-profile, high-pressure work, Sylvia seemed to project a steady, straight-from-the-shoulder vibe, even while she sat calmly at our table in the midst of a busy restaurant. As our conversation continued, she described several previous salvage jobs that had been considerably more challenging than the one arising from the Golden Ray debacle. Some involved big, highly publicized international catastrophes like the wreck of the cruise ship Costa Concordia in Italy in 2012 and the grounding of the semi-submersible rig Transocean Winner on the west coast of Scotland in 2016. But it was an anecdote she shared concerning the salvage of the Kulluk, a drilling rig driven onto the rocky shores of Alaska’s Sitkalidak Island seven years ago, that truly brought home the direct, reasonable, no-nonsense nature of her personality.

The Kulluk incident precipitated a world-wide uproar. When a broken towing cable allowed the rig to slam ashore during a sporty Alaskan winter, media outlets around the globe promptly began predicting a tremendous environmental calamity. Commentators and authorities alike foresaw a disaster on par with the Exxon Valdez spill, the worst in Alaska’s history. In keeping with this perception, the speed of the collective response was stunning. It took a mere 48 hours to assemble a Unified Command structure of roughly 800 people to deal with the crisis, many of them billeted at a big Marriott hotel in Anchorage. Stakeholders included the U.S. Coast Guard, Royal Dutch Shell (owner of the rig) and numerous federal, state and local agencies, as well as various branches of the military. Smit was hired to deal with the oil on board and reestablish a towing connection so the rig could be pulled off the beach and away to some safe location.

On the last day of 2013, Sylvia and a team of salvors boarded a private jet in Rotterdam bound for Anchorage International, many hours away. The plane arrived at 3 a.m. on New Year’s Day, and Sylvia spent the next four hours conferring with Anchorage-based officials. Then, at 7 o’clock, she caught another plane that took her to Kodiak where she boarded a helicopter to fly over and examine the rig. She returned to Anchorage late that afternoon.

“So, I had one of my longest days ever, something like 36 hours—and the most flight hours, I think, in one day,” Sylvia explained. “It was an interesting day. Obviously, access to the rig was not good due to its remote location. We would have to use helicopters for transportation and supply. And the days were short because of the winter. So, flight hours were limited and then the weather was amazingly bad at the time.”

A team of Smit salvors was nevertheless immediately airlifted to the Kulluk. But they soon discovered that living in the rig’s accommodation spaces over the upcoming days was going to be exceptionally uncomfortable, maybe even risky. For starters, everything was sopping wet—poorly designed windows had failed, thereby allowing the elements to intrude. Temperatures were well below freezing, and there was no electricity to supply heat. Moreover, there was no hydraulic power for winches and other machinery.

This last detail was critical. While the salvage crew figured that dealing with the oil on board would be relatively easy, reestablishing a towing connection between the rig and a giant towboat standing by offshore would be both slow and difficult. Lifting and manipulating tons of steel towing cable with hydraulics was one thing. Trying to do the job with chainfalls and other hand tools was quite another.

The weather worsened. The crew’s food and water ran low, and temperatures dropped even further. Initially, officials refused to fly more food and a genset to the rig due to the rowdy conditions. Then, to make matters even more difficult, the officials decided to call off all resupply efforts until the salvors had finally completed the towing connection.

“It took effort and convincing to persuade them to reconsider—to get them to see the whole picture, which is always what really counts,” Sylvia said, with a level, unblinking gaze. “To encourage them not to wait, but to deliver the goods required for the team to survive and gain spirit to continue the work. To explain that, because there was no power, everything had to be done manually and slowly.”

The staunch, albeit diplomatic, approach worked. In short order, Sylvia said, supplies were airlifted to the Kulluk, and a 6,000-foot featherweight Dyneema floating tow line was flown in from Holland to replace the steel cable that was so heavy and difficult to deal with. Not long after the new tow line arrived, the Smit team was able to complete a hookup and, within a day or so, facilitate getting the Kulluk pulled off the island and into the history books.

Sylvia and I had enjoyed a very long conversation by the time I admitted I’d never actually laid eyes on the remains of the Golden Ray, although I’d seen numerous photos and videos online. She looked around the dining area with a bemused expression—you had to admit, it was a rather oddball venue for the sort of subjects we’d been discussing—and made a suggestion.

“We can drive to the pier and look at the Golden Ray if you want,” she said. “You can take your car and I will take mine. And we will say goodbye there, please. I have a meeting with the Coast Guard soon.”

“Sounds good,” I replied.

The drive out to Jekyll Island fishing pier was a genuine eye-opener. I suppose I’d been lulled into a state of tranquility by Sylvia’s relaxed, straight-forward manner at McDonald’s, but once she’d zipped across the restaurant’s parking lot and jumped into that little white rental car of hers, everything changed. I was no longer dealing with an interesting, worldly, unruffled, top-of-the-line seafarer; I was trying to keep up with Mario Andretti. By the time we hit the Sidney Lanier Bridge, the little white car had flat-out disappeared, and I had nary a doubt—Sylvia Tervoort was not the type of person to dawdle along life’s highways and byways.

“Sorry to keep you waiting,” I said, when I finally arrived. “Sorta lost you back there.”

As we strolled out towards the end of the pier, my amazement at what protruded from St. Simons Sound grew by the second. Quite frankly, I’d never seen anything like it before, not in my entire life. The ship was laying out there, in flat, gray water, only a few hundred yards off, like a giant, grotesquely misshapen, semi-beached prehistoric whale. The incongruity of the sight was off-putting, almost disorienting. I stared open-mouthed for a minute or two and then, remembering the time, decided I’d better shoot some pictures of Sylvia with the unimaginable thing in the background. I didn’t want to make her late for her Coast Guard meeting.

“It’s a strange line of work you’re into, Sylvia,” I said as I clicked away. “Very strange.”

“Yes, perhaps,” she replied, nodding toward the wreck momentarily, “but whether it’s a car carrier like this one, or a cruise ship or a semi-submersible rig or a big wooden canoe in the Ganges River, the job is always fundamentally the same. It’s always salvage—I am always working on a rescue with the point being to help people, a vessel or the environment, whichever is in trouble. So maybe it’s not so strange, after all, Bill. Maybe it’s all just very simple.”