We reached out to photographer Billy Black for help telling a different kind of story: his own.

Famed portrait photographer Annie Lebovitz once said, “A thing that you see in my pictures is that I was not afraid to fall in love with these people.” That sentiment could be used to describe the career of marine photographer Billy Black, a man recognized on docks around the country for his crisp imagery and charisma.

Like many of you, I first came to recognize the name Billy Black from his photography bylines. It seemed that every issue I worked on in my early years featured his stunning photos. Knowing little else about the famed yacht photographer, I was certain of one thing: He was a master of his craft. I still remember meeting him on the docks of the Newport Shipyard; for me it was like meeting a celebrity. His humility was on full display from that very first encounter.

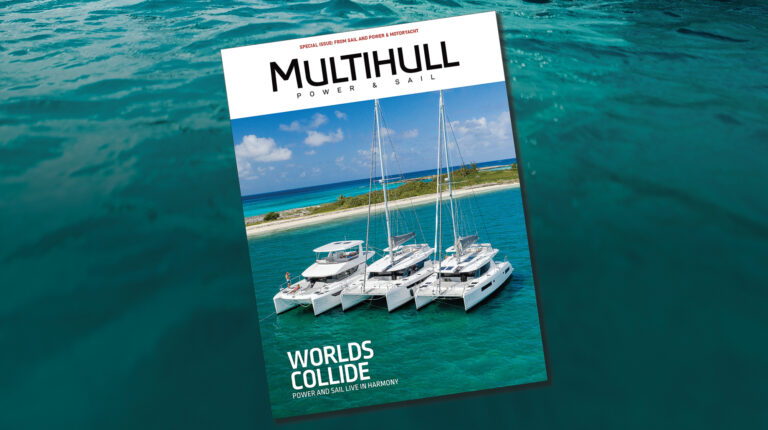

I’ve since had the opportunity to shadow and work with Billy many times. Together we brought the stories of countless boats and people to life, such as the Hood 57 LM, the beautifully restored Huckins Avocette and the Back Cove 39O. Then of course there’s this issue’s stunning cover shot he captured. Having admired his photos since I was young, it remains an honor to share a byline with him. Still, there is one story that hasn’t been told, a story of passion and photos, ups and downs, love and luck. That story is his own.

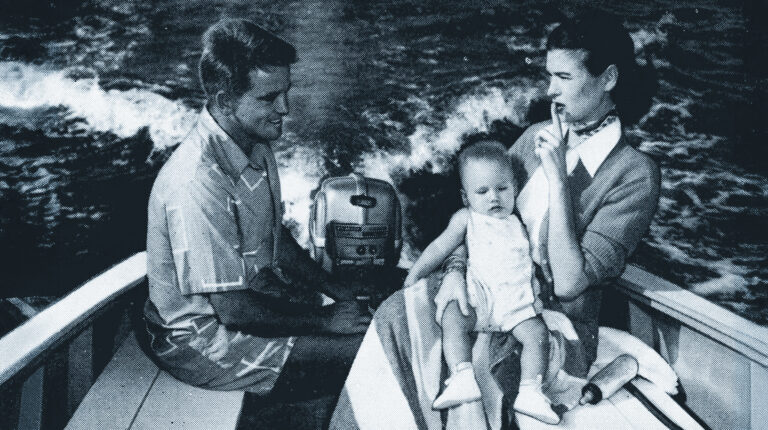

The son of a Navy lieutenant, Billy’s first foray into boating came when he was just a kid in the form of a mahogany runabout that his father built while working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Apparently, his father, a charismatic man in his own right, convinced a few laborers to help him build it. Billy would spend his formative summers aboard that runabout on a lake in upstate New York.

The two were close. So close, in fact, that in his early 20s he and his father bought an Erickson 39 sailboat together. They spent two memorable summers doing short-range cruising aboard her before his father became ill and passed away. Billy was just 25 years old.

“He put the boat in his will for me but made me promise to sell it as soon as it became an economic burden, which it did instantly, but I didn’t sell it for 20 years,” recalls Billy. “I just couldn’t part with it until it was really impractical.”

After his time in the military, his father found work in the shoe business. He hoped his son would follow in his dress-shoe-clad footsteps, a dream that was squashed when Billy called home from college one evening. He wanted to change tacks and pursue a career in photography.

“I thought I wanted to be a fashion photographer,” says Billy. “That’s why I started my career in Manhattan. I worked for some very famous fashion photographers as second and third assistants. But New York was tough back then. It was a real challenge.”

He eventually retreated from those mean streets and moved onto his boat. Soon after, he landed a job photographing a major refit at Derecktor Shipyard. A fortuitous encounter with Bob Derecktor changed his career course forever.

“Bob didn’t so much take me under his wing, but rather flapped his wings around me. He was a pretty strong individual. He didn’t speak to me at all for the first couple years until one fall we were on Long Island Sound doing sailing trials. He used to always have a fishing cap, like a tradesman’s hat. He loved that hat,” recalls Billy with a smile. “I was in my 14-foot Avon trying to take sailing pictures of this massive boat. It was pretty rough, and I was having trouble keeping up and then his hat blew off. I managed to get it out of the water, and then it took me another hour to catch up to the boat. When I finally got alongside the boat I threw it over to him. From that day on he remembered me. He had a newfound respect for me after that. That’s the way Bob was—you had to prove to him that you were worthy to be around him.”

The life of a yacht photographer is not as glamorous as it sounds. To capture images like the one above, Black has travelled hundreds of thousands of miles and spent countless nights in a van like this one, which is a recent–and major–upgrade for the marine shooter. Life on the road is not easy.

Derecktor introduced young Billy to others in the industry. He learned quickly that the boat business was the antithesis of the cold Manhattan fashion industry. “I fell in love with the whole extended family that we all know so well,” he says. “We’re all in business but there’s a commonality in the boating community.”

Despite having found what would end up being his lifelong passion, Billy admits that he struggled to manage the business side of photography early on. That is, until he met his wife, Joyce, whom he says is “one of the most unsung heroes in my life.”

For those lucky enough to know the Blacks, it’s clear they’re an inseparable power couple; two of the nicest people you’ll meet, their skills complement each other’s. It’s Joyce’s impeccable organization and business acumen that allows Billy to focus his lens on the creative side of the photos.

The two met in 1991 through a mutual friend. Shortly into their courtship, they would take on a last-minute boating assignment in frigid Zenda, Wisconsin, that would provide a true make-or-break moment.

“We went from Miami to Wisconsin; all we had was foul-weather-type jackets in a Midwest winter. We were all having a lot of fun out on the ice. Then a squall came up and we had no idea what the routine was. But what you do is hop on one of the boats and head back,” recalls Billy with a mischievous grin. “So, we all hopped on a boat except Joyce who ended up on the ice in a blizzard. I got back to the watering hole called Jack’s Place and had a beer and a hamburger and started relaxing, and after a while I realized Joyce wasn’t around. So, I borrowed an ATV to go find my girlfriend. In the meantime, she walked over to some guy’s fish hut and asked for a little protection. And he said, ‘Wait, your boyfriend left you out here and you think he’s coming back?’ She said ‘I know he’s coming back, because I have his camera bag.’”

The couple would settle down in Rhode Island; a locale that held a special place in Billy’s heart. A place that, not unlike his new romance, he had an inauspicious start with. Early in his foray into the world of sailing photography he set out from New York to Newport with his Avon strapped to the roof of his car to capture the conclusion of the Vendée Globe single-handed, around-the-world race.

“There was a terrific storm that night and the alternator decided to call it quits. The car died for the last time,” recalls Billy. “I called a tow truck and told the driver we need to go to Newport—I’ll pay whatever it costs to take me to Newport. We get to town and one tube of the Avon got punctured, rendering it pretty useless. We pulled into Goat Island at 5 a.m. It was raining and gray and cold. I was trying to patch the Avon with my bicycle pump and patch kit. Seeing [the winner] Philippe Jeantot come over the horizon was such a powerful moment. He looked a lot fresher than I did and he had just gone around the world—I went down the highway with an Avon on my roof. I knew then that this was going to be my subject matter for as long as I could.”

Jeantot would not be the only solo-sailor to make a lasting impact on the photographer. Billy became fascinated by the accomplished sailor Yukoh Tada, a taxi driver from Japan who went around the world alone in a boat he built himself.

“We had one great experience together during the Newport Jazz Festival. Yukoh was a jazz musician, so I asked if he wanted to join us on the boat. He said, ‘Oh yes, I’d love to come but I have a few friends. Can they come?’ Next thing I know there were 12 Japanese musicians, all with instruments, including a full-sized bass and trumpets. They piled in the Avon and came out to the sailboat, and between sets they would start jamming. Next thing people are swimming over to our boat, climbing up the freeboard and joining us. It was a riot. We had 25 people on this 40-foot boat.”

It would be a deep shock to learn that following his second solo race around the world, Tada committed suicide off Australia because he felt like he and his boat were failures. “That left such a lasting impression on me,” says Billy. “That someone so terrific would end his life so abruptly. It taught me to make the most of every experience.”

Perhaps Tada is such a fixture in the 64-year-old’s memory because recently he was forced to face his own mortality.

“The first time I found out I had cancer I was going to a boat show,” says Billy. It all started with his eye. As soon as he arrived in Florida he started to lose his vision. He turned around and went home, where he learned that he had lymphoma in his eye. He underwent a year of treatment, which was successful but cost him his vision in one eye.

With the cancer in remission, he went for a regular MRI checkup ahead of the Miami boat show (the boat shows are a pillar of his business). He arrived in Miami just in time to get word from a doctor that he needed to return home immediately. The cancer was back, this time in his brain.

For the next three to four months Billy would find himself in and out of Mass General for treatments.

“The doctors said the best thing to do when recovering was to walk. So, I would walk around the hospital and document what was going on around me. I would photograph other patients,” says Billy of perhaps his most profound photography project to date. “It was very different. I didn’t want to intrude on anyone’s privacy, but everyone was pretty much in favor of me taking photos. You don’t think of your appearance the same way when you’re a cancer patient. You think if I’m breathing, I look good enough. It gave me something that I felt good about doing. Just to be able to practice with a camera and remember how to use it. It was just a little one, just a point-and-shoot, but it felt good to use it.”

I was lucky enough to see Billy on one of his first yacht photo shoots after those treatments. He leapt onto the swim platform of the yacht with a huge smile. He reached out to shake the hand of the company president, who swatted his hand away and embraced him in a bear hug. It was as inspiring a sight as I’ve seen working in this industry.

“After I left the hospital, everything seemed more vivid to me,” says Billy about his return to work. “Everything was so much more vibrant. That was one of the great awakenings to see how much color there is in the world.”

You could hear all these stories and deduce that much of Billy’s prolific career has been the result of a healthy dose of luck. A career built from chance encounters, meeting the right people at the right time. You might be right, but I subscribe to the quote often attributed to Thomas Jefferson: “I’m a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it.” It’s his infectious personality tied with a work-ethic that he—of course—credits his parents for that has led editors, boatbuilders, sailors and hundreds of others to look forward to working with him.

“The most important thing to me is making good images, more than making a good livelihood,” says Billy. “I’m still fascinated by the subject, and I always want to do my best when someone trusts me with their photography needs.”