For a family of baseball players and fishermen, tradition is a way of life.

A line of trees grow on Canarsie Pier in Brooklyn. The son of an electrician and a nurse, Garrett Weir is just a sapling himself, young and wiry, but the boy shows a lot of promise. It’s 1995. He’s not quite 14 as he casts into the surf. After a beat, he leans his rod on the wrought-iron railing and stares intently at the water. As his mind wanders, the shimmering rollers start to take shape. Where only foam was just a second ago a sandy mound has risen. Kentucky bluegrass sprouts. Faceless shadows dig their cleats into a newly formed infield, staring him down. He picks up his rod. He imagines a fast ball, and that satisfying sound a baseball makes when it connects with a wooden bat at just the right spot. Thwack! His name lighting up the JumboTron. A crowd erupting in cheers. Fishing is his escape, but baseball is his calling, and together the two will propel him to heights he could only dream.

The trees have been replaced, and the boy is now a man, but not much else has changed as I stop by Canarsie Pier 25 years later. It’s 3 p.m. on a sun-dappled Friday, the height of summer, and the water’s edge is a flurry of activity. It’s not a pier as you might imagine—a long, wooden dock that juts out into the ocean—but a massive concrete peninsula with a parking lot in the center that is ringed by a shaded inner promenade. I park kitty-corner to a derelict sedan, all four of its doors wide open. A pair of shoeless feet dangle out the backseat. I head towards the iron railing, with its rusted metal bollards: the remnants of a commercial dock. Anglers, many of them solitary figures, have spread out along the pier, buckets and coolers tucked into tall, slender shadows. They cast close but not quite on top of one another, observing a silent social contract, like riding the subway car with strangers. Unlike riding the subway, here it’s understandable and in no way weird if one detects the distinct smell of fish.

Each angler seems to know his neighbor. The atmosphere is jovial but serious, determined but comfortable. At the end of the pier, an older fisherman is using a wooden table to fillet the day’s catch. A baseball cap shields his weathered brow from the sun. His head is tilted slightly as he grips a scaler in one hand, scraping it back and forth across a porgy. Dried blood covers the table. He picks up a serrated knife and leans into it, cutting horizontally. Another fisherman stands off to the side, watching him. All around them, good-natured smack talk is traded back and forth, while the occasional lure changes hands.

The pier is bounded by the Belt Parkway and Jamaica Bay, a partially man-made estuary separating JFK Airport from Coney Island. It’s a well-known fishing ground in New York, and one of a handful of spots the young Weir would pedal to on his bike. That plucky determination has turned him into a well-respected angler on Long Island, where he lives with his wife and two sons, the younger of whom shares his name. Competition got him here, but so did a laser-focus and a conscientious work ethic, all things he hopes to pass on.

Thirty minutes later I’m in Freeport, Long Island, shaking the hand of senior as junior eyes me thoughtfully. Garrett Weir Jr., or Little Garrett, is 6 years old and already a spitting image of his father. But his nickname might be something of a misnomer: Little Garrett is not so little. I need to keep reminding myself that junior is a kid. Easy enough when meeting him for the first time and seeing the shy attitude of a young boy. Not so obvious, however, when he takes the wheel of his father’s Steiger Craft 23 DV Miami with ease and points it towards open water.

The marshland of the South Shore is made up of low-lying islands and shallow bays. As we idle out of the canal and into the channel, Weir stands behind the helm, offering advice and guiding his son’s movements. The 23 DV has pilothouse seating large enough to accommodate a growing family. Fishing rods poke up out of the rocket launcher. Weir reminds his son to look both ways and watch for incoming traffic—breaking a fishing trip down into bite-size, teachable moments. He points out a shoal: “That’s shallow right there, so get back into the deeper water.” A 15-knot southwest wind is blowing, not the easiest conditions for a new hand. But Little Garrett appears easily coached. He asks thoughtful questions and adjusts the wheel accordingly to maneuver around the few other boats on the water. “This is when all the fair-weather fishermen stay home,” says Weir. “This is the best time to be out here.”

Weir isn’t one to stay home. The Steiger Craft is the first boat he’s owned, and he’s had it in his possession for only a few months. Even in that short time, father and son average about four days a week on it during the summer. The engine, a 250-hp Evinrude, has already seen over 242 hours. The prop never stops spinning.

That commitment imbues everything Weir does, and this 23-footer is a testament. Better than a trophy, he won the boat outright after winning a fishing competition. While other anglers casually competed for the main prize, trying to land the odd blackfish or fluke in their home waters, Weir was especially motivated. The year before, he lost in a tie-breaker, defeated by a rule stipulation. He was devastated. He had gotten so close to owning a boat, to having an outlet where he could make memories with his budding family, especially his 6-year-old son, who wakes up on his own to hit baseballs in the backyard. He vowed it wouldn’t happen again. So two years ago, he piled his fishing equipment into his car and scoured the Northeast in search of eight different species, traveling up and down the coast in his single-minded pursuit.

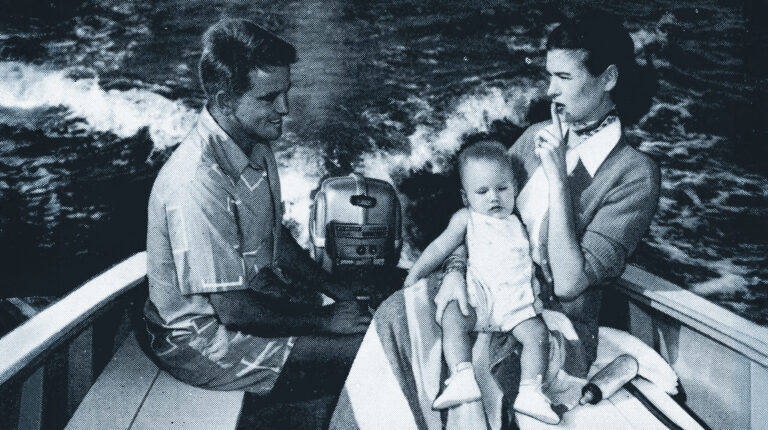

The founder of Steiger Craft, Al Steiger, has been building boats on the South Shore of Long Island since 1972, and was on hand to congratulate Weir after winning. He couldn’t help but see himself in the beaming, exuberant 38-year-old. “I’ve been fishing since I was 7 years old, and talking to Garrett, he’s been fishing with his father since he was seven,” said Steiger. “And now he has a 6-year-old fishing with him, so it really is a family tradition.” The Weir family takes it a step further: generations of men united by fishing and baseball, sports and the sea. But they make sure to never forget where they came from, either.

Back on the boat, Little Garrett is at the helm as we pass the Guy Lombardo Marina pier. A few guys stand with reels in hand, trying their luck. “Those guys are fishing right there, so we want to stay clear,” says Weir. “You make sure to respect the guys who are fishing from land. We don’t want to hit their line when they cast. They can’t move, but we can. So we steer clear.”

To the uninitiated, the Big Apple would appear to be a concrete jungle without a watering hole. Whether you’re dialed into the frenetic pace of New York City life, or have visited Times Square once to grab a T-shirt, it’s easy to forget that four of the five boroughs are islands with plenty of shoreline. If you want it bad enough, only a train ride away, trout can be found in the streams and rivers of the Catskills, and Long Island, a little closer, holds a cornucopia of different species inshore and off. Born into a middle-class family in south Brooklyn, Weir didn’t have many options available to him besides pier fishing. Both of his parents worked full-time jobs to keep food on his plate, so if he wanted to improve, he had to hustle. Weir would shovel snow all winter and stash his money away until summer. On the weekends, when he wasn’t engrossed in baseball, he’d pedal his bike 7 miles to Sheepshead Bay.

“It was the closest place,” Weir tells me. The closest also happened to be home to one of the most prestigious charter operations in the city. There, head boats would line up along the dock and captains would shout their prices into the air. “One person would say, ‘Hey, it’s $50!’” Weir says. “I would negotiate and end up getting on a boat for $35 bucks at 13.” Aboard each boat were a few sharpies—fishermen with good knowledge of the local scene. Weir would watch them and ask questions, tweaking his technique and learning from the best. Inshore fishing fueled his drive even more, freeing him from the confining limits of land and a city that never sleeps.

Weir’s dad, a Honduran immigrant who played softball with a local men’s league in his spare time, got him hooked on fishing. While most of his peers dreamed of becoming a professional football or basketball player, Weir, following in his father’s footsteps, pursued baseball. When he wasn’t on the field, Weir was something of a loner. At 16, his dad and uncle saved up enough money to go in together on a used Sea Ray. It ran pretty well for an old boat, and allowed Weir to fish even more. In an urban environment where most kids aren’t exposed to fishing or boating, Weir was the odd man out. “With fishing, I took it so serious that the other kids thought I was weird,” he says. “I never messed around. A lot of guys were like, ‘We’re going to go fishing’ and went to the beach to relax. I’m like, ‘No, dude. I’m going to fish.’”

His dedication paid off in more ways than one. In high school, Weir received a full scholarship to play baseball at Seton Hall University, where he batted leadoff and started as a left fielder. His sophomore year, he transferred to Delaware State University to get more of a college experience. But he kept playing ball, eventually graduating with an undergraduate degree and a master’s in sports management. His baseball career took him to Boston, where he played on a minor-league team for two years. He now plays semiprofessionally for the Nassau Pirates, and little Garrett is growing up in the dugout. The very real consensus among the players is that little Garrett is destined for the big leagues.

Out on the Steiger Craft, lines baited for fluke, we got skunked. It happens. Some days you knock it out of the park; some days you ground out. On our way back I watched a candid moment between the two Garretts. “I’m proud of you, man. I love you,” said the older one. He kissed his son. The younger one curled up and fell asleep. A home run.

When I spoke to Weir two weeks later, he was shopping for bean bag chairs to enhance the Steiger Craft. He had kids coming out for a ride, and they had seen a picture of little Garrett lounging on one. Of course he would accommodate their requests. He had also spent $120 on a collapsible grill that he found on sale. This was all in preparation of his growing charter operation. At first it was something he had started to do on the side, but thanks to a robust network of friends and family, business was picking up. On Friday, if the weather held, he had a client coming out to propose to his girlfriend in front of their families.

Owing to Weir’s background, a lot of friends and acquaintances were coming from the inner city, and many had never been on a boat before. For them, a cruise through marshland was a big deal. “I don’t usually like to mention race or cultural boundaries, but in the urban genre, a lot of us just aren’t exposed to boating,” he says. “I was exposed to it at a young age through fishing only. And we didn’t own a boat until I was in high school. We couldn’t afford it, and I didn’t have any friends that had boats.” Business was going so well, in fact, that he was seriously considering getting another boat, possibly a Tiara, and turning his charter business into a full-time operation. It’s hard to imagine a Steiger Craft going to a more deserving person.

A tree grows in Puerto Cortés, Honduras. He’s young and strong, with great ambition. He grows near the largest seaport in Central America, watching fishermen cast from their wooden boats. One day he’ll own a boat, he tells himself. He’ll work hard to achieve that goal, uprooting himself from the only place he’s ever known and journeying 5,000 miles north to the biggest city he’s ever seen. Upon reaching New York City, Ronaldo Weir will link up with some guys who play softball. The first day he’ll choose the number eight. Garrett, too, wore eight in high school and college in his father’s honor. And now, so does Little Garrett. When his grandfather saw him wearing his number at a little league game for the first time, he couldn’t help it. He cried tears of joy.

Taken from a 1943 seminal novel of the same name, “a tree grows in Brooklyn” is a saying used in the inner city to refer to the devotion, care and, frankly, luck, that propels a child forward in life. But not everyone makes it. A host of factors conspire against them, the most insidious being apathy. While Little Garrett is growing up in a more suburban area of Long Island, the same mentality applies. “You plant a seed, you water it and you watch it grow,” says Weir. “And as it grows you have to prune it and take care of it.”

Weir once said: “Fishing isn’t as easy as just putting a worm on a hook and throwing it out there and hoping you catch a fish. Fishing gets extremely detailed, and the more detail-oriented you become, the better fisherman you become.” It’s good advice. But I wanted to know if there were any similarities between that statement and fatherhood. How important are the details, the little things, to being a good dad? He pauses for a second. “It coincides directly,” says Weir. “You have to be focused. You have to pay attention to his needs, his wants. That emotional love that I know my dad had for me, that resonated with me. I now try to give it to him every day. If we’re fishing and he says, ‘Dad, I’m tired. I want to go home,’ I’ll pick up on an epic bite and leave. At 6 years old, I can’t force him, because I know that if you force a kid too young—that’s it. He’s not going to want to do that anymore. That’ll be the worst thing I could ever do.”

“But you know, he’s young,” continues Weir. “He may not like baseball in five years. He may want to play basketball. He may say, ‘You know what, fishing is great, boating is great, but I don’t want to fish anymore. I just want to boat.’ I’m just trying to do my best to keep him exposed to things and go from there. If he picks it up, he picks it up. If he doesn’t, he doesn’t. I’m just happy to be spending time with him, and right now, our interests coincide.”