Edgy, Edgy, Edgy

Marquis’ 420 sport bridge offers rad styling, pod propulsion, and all-American construction.

There are plenty of skippers who are seriously into making a statement every time they bring a boat into a marina, especially when it’s a marina they’ve never visited before. The statements vary, of course. A Grand Banks owner like myself, for example, loves showing off his classical, down east sensibility. Others enjoy announcing their sentiments with swoopier, more modern themes from builders like Cruisers, Regal, and Sea Ray. And then there are those who go in for full-bore, head-snapping edginess.

It’s this latter bunch the Marquis 420 Sport Bridge was designed for, I’d say. Compliments of Nuvolari-Lenard, a naval architectural firm based in Venice, Italy, her exterior styling is totally and absolutely “rad,” as they say, boasting a complicated mix of straight and curved style lines that engenders pure exoticism, particularly in profile. More to the point, her sheer is virtually straight, breaking upwards before diving aft, and raffishly aquiline at the bow. And stacked atop that sheer, there’s a striking array of dark, arched windows and windshield panels, a jauntily swept-back superstructure, and surmounting everything, a venturi windshield in two parts, both angled aggressively forward and supported by stainless steel rails.

“Wild-lookin’ boat,” I told Darren Matthews of Singleton Marine Group, Marquis’ dealership on Lake Lanier, a vast, pine-studded reservoir in northern Georgia. We were both standing at the stern of the 420, grateful for the shade her big, open-sided house offered us. It was July, mid-morning, and temperatures were already on the rise as we jumped aboard.

The boat’s interior was just as striking as her exterior. Bright and inviting due to both an assortment of wraparound windows and a hinged, safety-glass door in the back bulkhead, the saloon seemed to capture the essence of modern residential eurostyle. It featured crisp, baseball-stitched upholstery with contrasting brown ultraleather and white ultrasuede surfaces (undeniably chic but perhaps a tad tough to keep clean long-term) and an overall appearance that promised comfort with Lamborghini-like flair. Indeed, the standard lower-helm station, just forward of the dinette and to starboard, had an automotive feel to it, complete with a three-spoke, race-type wheel, a black, leather-trimmed dashboard, and a seat I could electrically adjust every which way but loose.

The galley continued the theme. Opposite the helm station, it both augmented and domesticated the ambiance there, offering metal-flake solid-surface countertops, sculpted stainless steel fiddles, and a matching set of metallic-gray cabinet fascias, in addition to a full complement of stainless steel appliances.

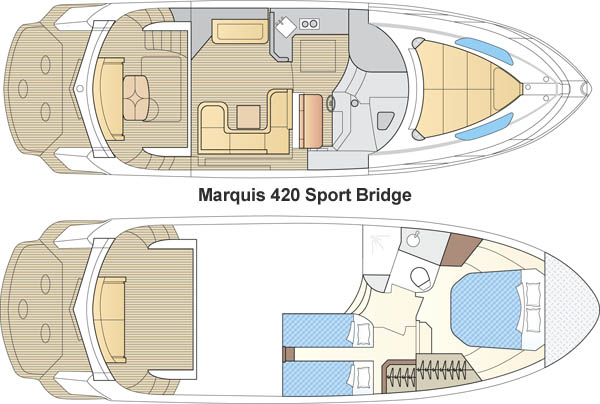

Although the two-stateroom, one-head layout below was fairly conventional in comparison with arrangements topside, the panels and fabrics were precisely selected to ensure a coordinated, albeit avant-garde, appearance. Especially practical, by the way, were the pillow-top innerspring mattresses both on the island berth up forward in the master and on the two side-by-side berths in the guest stateroom on the starboard side. Nothing beats a decent night’s sleep, whether on the water or off.

A hot boat deserves a hot testing venue, I always say. So, in keeping with the gist of this trusty apothegm, I managed to sea trial our 420 that very afternoon with the thermometer pushing 100F, nary a breath of air nor a ripple to be seen anywhere.

One thing stood out from the onset. While the 420 is oh-so-Italian in terms of styling and design, her essence is purely and undeniably American, the end product of processes that the boatbuilding folks in Pulaski, Wisconsin, have been honing for decades. Performance was the biggest indicator of this. With her twin 435-mhp Volvo Penta IPS600s throttled up to full chat, our test boat ran like she’d been sent for, producing an average top hop of 37.8 mph and sweeping through a series of thrillingly tight, crisply banked turns with resolute composure. At one point I estimated the tactical diameter of one of these turns to be no more than two boat lengths and attributed such sprightliness to an expertly balanced longitudinal center of gravity (running attitudes were optimum throughout the rpm register) and the extremes of articulation that pod-type drive units are typically capable of.

While sightlines at the lower helm station were a tad limited when looking forward, mostly due to the thickness of the test boat’s window and windshield mullions, the dash was easily readable, and both Matthews and I totally—and I do mean totally—appreciated the 38,000-Btu Cruisair air-conditioning system onboard, which did its job with frosty gusto. Topside, visibility at the helm was 360-degrees-excellent, the dash was easily readable as well, and conditions, while certainly not cool in the meteorological sense, were still quite enjoyable, especially at full throttle.

I had only two problems. First, the Awlcraft 2000-top-coated welded-aluminum radar arch behind the helm was too low to keep my head below the radiation a scanner would emit. Certainly, a skipper could nix the issue by going with the lower station during periods of poor visibility, but that would restrict sight lines and presumably cut back on overall radar usage. Why not raise the arch? And second, I noticed our 420’s running lights were mounted at deck level, on the bow, in close proximity. I’d like them mounted higher, on either side of the flying-bridge cowling, making them easier to spot at night.

Dockside maneuverability was excellent. Backing the 420 into her slip using the IPS joystick on the bridge was a cinch, not only due to the glories of pod-type propulsion but also to the positioning of the joystick itself. As a right-hander, I could simply rise from the helm seat, face aft (with my butt against the steering wheel) and use my most dexterous digits in complete comfort. A southpaw could have enjoyed the same thing, merely by standing on the other side of the control.

One more detail’s worth mentioning. Before departing Singleton Marine Group’s lovely facility, I spent a half hour or so examining the engine room. Crisply painted bilges; diamond-plated walkways; tinned-copper wiring loomed into precisely labeled, color-coded harnesses; ancillaries from mainstream companies like Glendinning, Marinco, Charles Industries, Deka, and Parker Racor—everything I saw was all-American, all the way.

“The machinery spaces are as conventional as mom and applie pie,” I told Matthews as I climbed sweatily out, “But styling-wise? This baby’s edgy—and I mean edgy, edgy, edgy!”

Click here for Marquis’s contact information and index of articles ▶

Brokerage Listings Powered by BoatQuest.com

Click to see listings of Marquis Yachts currently for sale on BoatQuest.com. ➤

The Boat

Layout Diagram

Standard Equipment

Volvo Penta electronic steering and controls w/ 2/joysticks; Quick windlass w/ Davis anchor and chain and 2 remotes; Clarion stereo system w/ speakers; Vitrifrigo refrigerator; Euro Kera 2-burner cooktop; Contour microwave oven; Sol LCD TV w/ stereo/DVD/ CD player and iPod link and Sirius service; VacuFlush MSD; 10kW Kohler generator; 38,000-Btu Cruisair A/C; 6/Deka Marine batteries (2 cranking, 3 house, 1 genset); 2/Charles Industries battery chargers (60-amp for engines and house and 20-amp for genset); Charles Industries Iso Transformer; 2/Racor 900MA fuel-water separators; 11-gal. Seaward water heater; Lectrotab trim planes

Optional Equipment

Raymarine ST70 autopilot w/ remote; Raymarine electronics (including E90W multifunction nav display, 240 VHF, and DSM 300 sonar module); Avanti ice maker; Marquis lead-crystal glasses, china, and flatware; Glendinning CableMaster; upgrade to 13kW Kohler generator; teak decks on cockpit, swim platform, and flying-bridge stairs

Other Specification

Cabins:1 master, 1 guest stateroom

Specifications

- Optional Power: 2/400-mhp Volvo Penta IPS550Gs; 2/435-mhp Volvo Penta IPS600s

- Water Capacity: 140

- Overall Length: 43’7″

- Beam: 13’11”

- Fuel Capacity: 300

- Draft: 3’7″

- Year: 2011

- Type: Product+boattest

- Standard Power: 2/370-mhp Volvo Penta IPS500s

The Test

Test Boat Specifications

- Test Engine: 2/435-mhp Volvo Penta IPS600s

- Transmission/Ratio: IPS-E gears/ 1.82:1 ratio

- Props: IPS T3 propsets

- Price as Tested: $920,000

The Numbers

| rpm | mph | knots | gph | mpg | nmpg | range | nm range | db | angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 1.6 | 4.78 | 4.16 | 1291 | 1123 | 60 | 0.0 |

| 1500 | 9.9 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 1.62 | 1.41 | 438 | 381 | 65 | 0.5 |

| 2000 | 12.2 | 10.6 | 14.5 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 226 | 197 | 68 | 3.0 |

| 2500 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 23.0 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 227 | 197 | 72 | 3.5 |

| 3000 | 27.9 | 24.2 | 29.5 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 255 | 222 | 72 | 3.5 |

| 3500 | 36.6 | 31.8 | 40.0 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 247 | 215 | 74 | 3.0 |

| 3630 | 37.8 | 32.9 | 43.5 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 235 | 204 | 76 | 3.0 |

This article originally appeared in the November 2011 issue of Power & Motoryacht magazine.