It’s Electric

After installing Dometic Optimus electric steering, the author rides high on what he calls “the wave of the future.”

Dometic’s Optimus Electric Steering Actuator represents a major change to a critical system, and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to call it the future of outboard steering. I installed Dometic’s electric steering on my 22-foot center console, and it has delivered on the promise of simple installation and operation while allowing precise control, minus the messy hydraulics.

My 22-foot Cobia came with a well-used—and at the time, leaking—BayStar hydraulic steering system. Replacing the seals on the hydraulic ram resolved the leak, but the steering was still not very responsive, and a lot of effort was needed to make a turn, even after purging the system twice. Frankly, I had had enough. I’d seen Dometic’s system after it debuted last year and wanted to install it in my center console.

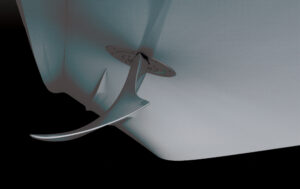

The Optimus system consists of two primary components: First, the electric actuator at the stern that connects to the outboard (one per engine) and second, the electronic, drive-by-wire helm unit to which the steering wheel mounts. The electric actuator turns the motor by spinning roller screws inside the threaded body of the actuator. The system also has a display and wiring harness. The wiring harness connects to the side of the actuator, the boat’s batteries, the helm unit and the boat’s NMEA 2000 network. There are three CANBus networks running; two are used for communications between helm units and the actuators, and the third communicates with the boat’s NMEA 2000 electronics. The Optimus display is currently required for all installations. You can also add a joystick with multiple engines for easier maneuvering, dynamic positioning and autopilot. The joystick includes a high-precision attitude, heading and position sensor package to accurately maneuver the vessel.

Before beginning the installation, I was mostly concerned with pulling the large wiring bundle through my boat. Fortunately, Cobia built the boat with a 4-inch PVC rigging tube that was only about half full. Between the relatively empty chase, the use of fiber-glass fishing rods and the assistance of my petite, 12-year-old daughter Molly (who I parked upside down inside the console to grab the wire bundle as it came through), the wiring -harness was quickly in place.

Emboldened by my success pulling the wiring, I moved on to testing the setup with the components in the boat. Before ripping out the existing Baystar system, I wanted to make sure the new one was going to work. I was able to make it as far as the display wanting to calibrate (which I skipped because the actuator was not secured), and everything looked good. I had to drain the old hydraulic lines and take the ram off the motor. That last part turned out to be the hardest step in the entire install. It took lots of pushing, pulling, pounding and an errant wrench to the forehead to free the old, corroded ram.

Installing the actuator was as simple as following the diagram and making sure all of the washers, spacers and nuts fit in the right place. The final task was connecting the ram to the tiller arm. By the grace of something, I didn’t drop the bolt, nut or washer in the drink, and everything bolted together nicely.

All that was left at that point was making the final connections, which consisted of battery cables, helm and display connections and a NMEA 2000 network connection. Calibration was a two-minute job which required little more than turning the steering to each lock. Six hours after starting, I had the entire system in place, including a new hole in the dash for the Optimus display. I was pleasantly surprised at how easy the system was to install and excited to try it out.

After extensive dockside testing the following morning, I dropped the lines, backed out of the slip and went for a spin. If you’re expecting me to report on some inherent issues, then you’re going to be disappointed. The system has worked -perfectly. I’ve logged more than 60 hours and 700 nautical miles on the water with the new steering with zero troubles; it’s precise, intuitive and easy to use.

My direct basis for comparison is the well-used Baystar hydraulic steering, which had a worn helm pump that made the turning effort asymmetrical, with turns to port requiring much more effort than starboard. This added up to a fatiguing experience, especially in slow zones where more corrections are required to keep the boat straight. I could have replaced the old helm pump and resolved some of my issues with the existing steering, but I wouldn’t have enjoyed the many benefits of electronic steering.

With the electronic helm, a slight turn of the wheel corresponds to a precise movement of the outboard. There’s no sloppiness at all, and effort is always the same. You can also adjust the number of turns lock-to-lock at low speed and high speed. (I’ve set my steering for four turns lock-to-lock at low speed and six at high speed.) I’ve also set the steering effort at 60 percent at low speed and 85 at high speed. I like a stiffer wheel than the default settings, and it was very easy to tweak it to my preferences.

When the ignition is off, the actuator has a mechanical lock that firmly holds the motor in place. I’ve yet to see the motor move from a following sea, wake hitting the stern or any other force. This control has nearly eliminated any worry of unintended turns, even if I take my hands off the wheel for a moment. Before, when I tilted the engine out of the water, the outboard would slowly fall to one side or the other and rest on the stops. With electronic steering, the motor never moves unless you turn the wheel.

My Yamaha 150 has a 35 amp alternator, and I paid close attention to how much power the actuator consumed. My testing never saw consumption above 16 amps, and even those levels were -fleeting. When the motor isn’t turning, it uses less than 2.5 amps when -underway and much less when stationary.

Calling out one product as the future of such a broad category as marine steering may seem bold or even silly, but if the price can be brought down, I feel this system will become the new standard. The precise control, simple operation and easy integration are all compelling—as is the absence of hydraulic fluid, pumps and lines.

The single engine/single helm configuration for my boat carries a list price of $5,200. Dometic says a typical twin-engine installation with a joystick would cost $18,200. The company says it plans to bring the cost down and is working on offering simple installs without displays. I’d also like to see a simpler, less-expensive autopilot for installs that don’t have the joystick and an anti-theft PIN when the display is -present. An added level of security (not possible with other steering options) would only increase the value of electronic steering.

Overall, I’m thrilled with the system and look forward to years of trouble-free, reliable steering.