Joy(sticks) to the World

Got serious docking angst?

Need a cure for technology envy?

Install a joystick, and get on with life.

Here’s what you need to know.

I’d rather shoehorn a 100-foot tugboat into a 102-foot berth bookended by gold-plated megayachts than dock an outboard boat in any kind of crosswind. With high freeboard forward and not much hull form under the water, outboards just go all over the place. They’re almost as bad as sailboats. And it’s even worse with two, three, or even four big four-strokes hanging off the stern. Talk about unbalanced! So you can imagine my reaction the first time I saw a skipper in a shiny new center console slide sideways into a tight spot at a fuel dock using a joystick, doing it all with a flick of his wrist and minimum angst. I instantly developed a bad case of technology envy—I wanted that joystick!

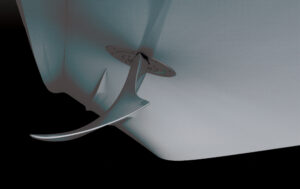

The system is steer-by-wire all the way back to the transom where actuators hydraulically move the tie-bar-less outboards.

The essence of outboard joysticks:

two motors that rotate independently.

And now, thanks to the engineers at SeaStar Solutions (www.seastarsolutions.com), I can have one, and without trading up to expensive new engines. Introduced as a Teleflex Marine product, the Optimus 360 joystick control system can be retrofitted to twin, triple, or quad outboards with mechanical or digital controls. (Contact an authorized Optimus dealer for specific compatibility questions; search on the SeaStar Website for one near you.) Optimus 360 is based on SeaStar’s Electronic Power Steering (EPS) system, a worthwhile upgrade in itself; more on this in a little bit. Adding the joystick introduces independent (meaning tie-bar-less) engine rotation for ballerina-nimble maneuverability. It’s a cure for both docking insecurity and tech envy. You know you want it.

But hold on a minute, matey: Installing Optimus 360 involves a lot more than simply mounting the joystick and plugging in a couple of wires. This is high-tech stuff, with lots of computers, controllers, actuators, and such—in other words, expensive components. SeaStar insists Optimus 360 be installed by one of its authorized dealers—DIY-ers need not apply—which adds technician fees to the equation. So, you’re probably asking, what will this cost me? There are a lot of variables, but based on my conversation with SeaStar’s public relations rep, I’d say don’t expect to get much change back from $20,000 for a typical installation—and don’t be surprised if you have to pony up even more. That ain’t cheap, but neither are proprietary joystick controls like those from Yamaha or Mercury, and you have to buy the appropriate engines first. Compared to that kind of investment, Optimus 360 is a relative steal, especially if your present outboards have a lot of hours left in them. We only go around once in life, so why not do it with a joystick?

The latest and greatest CANtrak display offers real-time rudder direction and rpm info.

Drive By Wire

The primary component of Optimus 360 is EPS, which replaces your boat’s existing hydraulic steering. EPS is hydraulic, too, but the pumps and oil lines are located near the engines; from there forward it’s steer-by-wire, controlled by an electronic helm. (No more topping-up the steering oil at the helm, and spilling it all over the dash.) EPS can be retrofitted to outboard, stern drive, and inboard boats up to 70 feet, and has enough advantages to be worth considering even for single-engine boats. The electronic steering is speed-sensitive, both in terms of wheel effort and number of turns. For maneuvering at low speed, the steering is easier and quicker, meaning less cranking on the wheel lock-to-lock; at planing speed, it’s stiffer and less sensitive for more delicate steering input. Both settings are operator-adjustable.

Installing a second steering station or autopilot is plug-and-play, as long as you choose the right pilot; consult with your electronics guru on this. You don’t need a separate pump for the pilot; it uses the digital steering circuitry. However, your present autopilot probably won’t work with Optimus EPS. Because there’s no tie bar between the motors, which have to pivot independently to use the joystick, an autopilot connected to one engine will turn only that engine. (SeaStar says the Optimus Pump Control Module, the black box that’s the brains behind EPS, “accommodates certified third-party autopilot systems,” so there might be a workaround for this. I wouldn’t be too optimistic, though.) Optimus EPS uses two SmartCylinders with integrated rudder-feedback units, driven by two hydraulic pumps, one set for each engine in twin installations. The electronics keep the engines in line based on feedback from the SmartCylinders—it’s a virtual tie bar. Each SmartCylinder and pump have the muscle to control two motors, so in triple- or quad-motor installations, the motors are connected physically with tie bars, in either a 2 + 1 or 2 + 2 configuration.

Sea-Star’s SmartCylinder does not need an extra rudder-feedback unit for an autopilot intall—it’s built-in.

A Matter of Leverage

One disadvantage of many outboard- or stern drive-powered boats is the proximity of the propellers: They are mounted almost blade tip to blade tip, which takes away much of the advantage of your typical twin-screw inboard when maneuvering in tight spaces. In such an application, the props are much farther apart, which increases leverage and produces more turning effect when splitting the shifts. Add to this the torque effect of the props and the steering effect of the rudders when given a blast of forward prop thrust, and a skilled boat handler can lay a twin-screw inboard alongside as neat as you please.

But put the same old salt in a boat with pivoting drives, whether outboard or sterndrive, and he may have his hands full. It’s due not only to the narrow separation of the props, which demands a lot more throttle to get the boat spinning on her axis, but also to the direction of thrust. With inboards, the propwash over the rudder with the engine in forward has a much greater effect than the same throttle setting in reverse. So, when maneuvering a twin-screw inboard, you set the rudders according to the engine running ahead. If, say, you want to spin to port, you crank the wheel to port, put the starboard engine ahead, port engine in reverse, and the starboard engine and rudder essentially turn the boat while the port engine complements the spin and keeps the boat from moving ahead. You don’t have to worry that the port rudder is turned the wrong way—it’s not having much effect.

But a sterndrive or outboard aims its thrust whether in forward or reverse, so the engine in reverse almost cancels out the one in forward. In the same maneuver as described above, the thrust from the starboard engine turns the boat to port, but the reversing port engine drags it back again. (In the meantime, the wind’s caught the bow and you’re heading off to who-knows-where!) Better to leave both drives amidships and push down on the throttles to spin the boat, despite the so-so leverage of tightly spaced engines.

That’s what’s so great about systems with independent drives: Aimed or directed thrust becomes an advantage, not a curse. And the joystick makes it all intuitive. Even old salts can figure it out.

Shift By Wire

But EPS is only half of Optimus 360; digital engine controls (DEC) are also necessary. The joystick is really just a switch, or an array of switches—it can move electrons, but not mechanical shift and throttle cables. Many new-ish outboards have electronic controls already, so adding Optimus 360 is basically a wiring project: You use the existing DEC circuits and plug in the joystick and CANtrak control panel.

What about engines with mechanical controls? There’s a workaround for them. The Optimus 360 MST (Mechanical Shift and Throttle) option replaces the boat’s existing controls with SeaStar’s i6800 shift and throttle. The electronic i6800 is wired to external actuators mounted near the engines and connected to them with short mechanical cables, one shift and one throttle actuator for each engine. The i6800 signals the actuators, which then manipulate the short shift and throttle cables connected to the engines. As far as the engines are concerned, nothing has changed—they’re still cable-controlled—but at the helm, the i6800, joystick, and control panel are digital all the way.

Once the electronic controls are installed, the rest is essentially plug and play, although there’s some initial programming and setup involved. For example, the computer has to be calibrated so when spinning the boat, the engine running in reverse revs a bit faster than the one in forward—since the props are more efficient turning ahead, if the rpm is the same on both engines, the boat will turn in place but simultaneously move forward in a slight spiral. (Folks with twin-screw inboards know of this effect.) To use the joystick, just push the ‘Command’ button to turn it on, and remember to keep your hands off the wheel and shift levers. Until you get the hang of it, that’s easier said than done. When the joystick is active, the steering becomes hard to turn, so if you forget, the increased resistance will remind you. Simply switch off the joystick with the Command button or by moving one of the control levers.

Anchor By Wire

Since its introduction five years ago, Optimus 360 has evolved continually and now has almost all the capabilities of brand-specific electronic joystick controls. But until October 2016, when SeaStar introduced SeaStation GPS, the system lacked station-keeping—for some people, one of the handiest features of electronic control systems. Like Mercury Marine’s Skyhook and Volvo Penta’s Dynamic Positioning System, SeaStation GPS keeps your boat in one place while you fish, arrange dock lines, wait for a spot to open at the fuel dock, make a sandwich, or whatever.

Consisting mostly of a dual-channel GPS sensor and some software upgrades, SeaStation can hold position, heading (good for drift or kite fishing), or both. Folks already using Optimus 360 probably wondered what the “A” and “C” buttons on the joystick were for; they activate the SeaStation modes. The new software controls shifting, steering, and throttling more effectively, according to SeaStar, both minimizing changes and making them happen as smoothly as possible.

A word to the wise: A joystick can’t offset inattention, foolishness, or just plain bad luck. More to the point, I’ll use my new Optimus 360 and SeaStation to hang in the channel, waiting for the wind to drop before docking. I know the joystick is supposed to make it easy as fish pie, even for old-time prop-and-rudder guys like me, but I’m not taking any chances; I’ll wait for the expensive boats to move on, just in case I flip the joystick the wrong way. In the meantime, if you have a tug or small harbor tanker you need moved alongside, let me know. No joystick required for that.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Power & Motoryacht magazine.