Log It: On extended trips, keeping a proper logbook is essential. Entries should include position, speed, magnetic heading, rpm, and engine-coolant temperature. Also, log every fuel purchase.

Did You Say Something? Communication is key. Your mate can’t hear you speaking into the wind

while they’re on the foredeck. Come up with hand signals and invest in a wireless headset.

Learn more from Senior Electronics Editor Ben Ellison aboutCruising Solutions My Team Talks Bluetooth headsets here. ▶

File It: Always file a float plan with someone who will know how to manage the situation if you don’t turn up.

www.floatplancentral.org

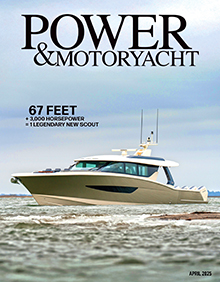

I Can’t Hear You: I’ve been running boats since I was eight, ranging from a skiff to a 112-foot motoryacht (such as a Westport 112, shown). I have a lot to learn still, but feel pretty confident that I can dock a boat. So why I listened to the 18-year-old college girl screaming orders at me as I docked in Nantucket I’ll never know. My perfect entry ended in complete chaos. Trust yourself. Chances are that dockhand has never really docked a larger boat. — George Sass Jr.

Mark Your Spot: I find it helpful to etch in the optimal engine-coolant temperature on my analog engine gauges. I can see my vital signs with a quick glance. For electronic gauges, a label maker is a useful tool.

— George Sass Jr.

Safety is no secret: You may have multiple ways to send distress signals on your boat, such as those offered by the DSC-enabled VHF, satellite devices such as the Iridium GO, helm electronics, and even iPhone apps. Make sure your crew knows how to use them, in case you become incapacitated. — Jason Y. Wood

Reach Out: If you’re unsure of a commercial vessel’s intentions and course, give them a shout on Channel 16 or Channel 13 if you’re relatively close. AIS has reduced the guessing game, but if you want to determine which side to pass a tug and barge, the captain will gladly tell you.

Know Before You Go: Take the time and input your route and/or waypoints while at the dock. Doing so while lost in the fog is not the way to navigate. Trust me, I’ve done it too many times. — George Sass Jr.

Stay the Course: Don’t forget about your compass. And remember a compass indicates your course. GPS indicates your position. Make sure you have an updated compass deviation card.

Light Up: Make sure there is a small flashlight for every crewmember and one next to every berth.

You can never have too many onboard.

Condition Response: In bad weather, cut your speed, particularly if you are encountering headseas. You may be able to proceed in fair comfort at half throttle but snap antennas off and pound at two-thirds throttle.

Know Thy Boat: It’s important to understand your boat’s limitations in heavy weather. A poorly designed 60-footer may be uncomfortable in a 3-foot chop while a properly designed 35-footer may do just fine.

Just Drive: In rough weather, consider disengaging the autopilot and driving the boat.

You’ll get a feel for your boat and the wave pattern.

Burn Unit: One hand for yourself, one for the ship when navigating a smokin’ hot engine room.

Smart Speed: Don’t be afraid to slow down when negotiating a fleet of small boats, especially at night.

Gives you more response time.

Clear Course: Pay attention to the color of the water around your boat.

If it’s brown, you may not be in 50 fathoms, no matter what your depthsounder says.

Aft Aware: Don’t forget to look behind you, especially at night, and especially if your pilothouse has small or no rear windows. Running a boat from an open flying bridge is almost always safest.

Glass Bridge: Don’t forget. Your electronic cartography is virtual. What you see out your windows is real!

Look Ahead: Use several ranges on your radar when running at night.

Get a good feeling for what’s 6 miles ahead, 12 miles ahead, even 24 miles ahead.

Dream Team: Try never to navigate alone at night.

Have someone sleeping on the settee in the wheelhouse. Just in case.

Current Events: When navigating a narrow channel, avoid getting set out of the channel by a cross current

by looking at the markers behind you as well as ahead.

Tune in: Be aware of how your boat sounds, perhaps almost subconsciously.

If engine pitch, or something else changes, it could spell trouble.— Capt. Bill Pike

Let’s Talk: I’m amazed at watching people come into a slip or leave the dock without speaking.

My wife and I go through exactly what we’re going to do before touching a line. The result?

We’re completely in sync and even if guests are on board, we just handle it ourselves. — George Sass Jr.

In the Know Below: On long trips, never venture into your engine room for a regular engine-room check at night unless someone else knows.

Take a Walk: It sounds obvious, but take a walk around your boat once you’re underway to double-check everything is secure, there are no lines in the water, fenders are up, and your ride is shipshape.

Heavy Lifting: What if you don’t have a LifeSling or some other device that facilitates

pulling a person out of the water? Go with a stout line looped under the arms instead.

Wet a Line: Never go overboard to swim or for inspection purposes, whether inshore or offshore, without a long safety line trailing. The strength of currents in the midst of the ocean is sometimes astounding.

Cold Comfort: If you fall overboard, especially in cold water, immediately assume a fetal-type position which will lessen the escape of body heat. Try to float, not swim, which expends both heat and energy.

Pee Smart: All alone onboard?

Need to visit the virtual restroom at the stern? Don’t do it! Use the real restroom instead. It’s much safer.

Splashdown: Someone just fell overboard? Hit the MOB button on your plotter and toss a lifering! No lifering? Toss a cushion or any other thing you think will float.

Personal Magnetism: Watch where you stow that pocket knife or screwdriver, fella. Plenty of folks have gotten totally lost because they screwed their compass up with some sort of metal object.

See the Future: Use your radar in a timely manner to determine if collision avoidance measures

will be necessary at night, especially where ships are involved.

Ships are typically fast and that 3-mile range is pushin’ it.

Safety First: Every boat should have an anchor safety strap to avoid unintentional deployment.

There was a case a few years ago where the anchor deployed, streamed behind the boat, caught ground,

then released, flying back into the cockpit striking and killing the guest. It’s worth the 50 bucks.

Location, Location, Location: Take your boat’s accommodations plan and indicate

where the through-hull fittings and fire extinguishers are located.

Post this in a prominent spot and ensure your crew is familiar with the diagram.

Give a Little: I was surprised on a recent weekend in Casco Bay when the captain of 35-footer started yelling at a trawler to get out of his way. Besides forgetting good manners, the captain forgot that the overtaking vessel is the give-way vessel.— George Sass Jr.

Heave Ho: Throw your dockline from your boat like a pro. After it’s secured to the cleat, coil neatly and then divide the coil in half. Leave about four feet of slack between the coils.

Heave the coil in your right hand over the head of the recipient on the dock.