On a clear, high-desert morning, water stretches out through a wide canyon like a sheet of hammered silver. Red rock cliffs climb from the shoreline, their faces cracked by centuries of sun and wind. It is far from my regular, brinier arena of reportage—which is, at least in part, why I’m not there, with the other reason being that a subject like Brandon Gross is hard to catch.

Our connection is weak, pixelated with lapsing audio, but we’re able to communicate enough to decide to reposition the boat and see if things improve. I can hear the groan of a four-stroke outboard. It grows louder as the rock faces along the glassy lake’s surface drift by, first with a lo-fi graininess, and then suddenly with a crispness accentuated by a stark, bluebird sky.

A fuzzy figure comes into frame as his lens catches up with the speed warp, but I can tell he’s pulling the throttle back and letting the boat settle. It coasts to a slow, listless drift. The focus settles on the landscape astern as Gross disappears momentarily, but I get the sense that this is my cue. I’m finally able to commence with my journalistic duty of interrogation: “Where are you?”

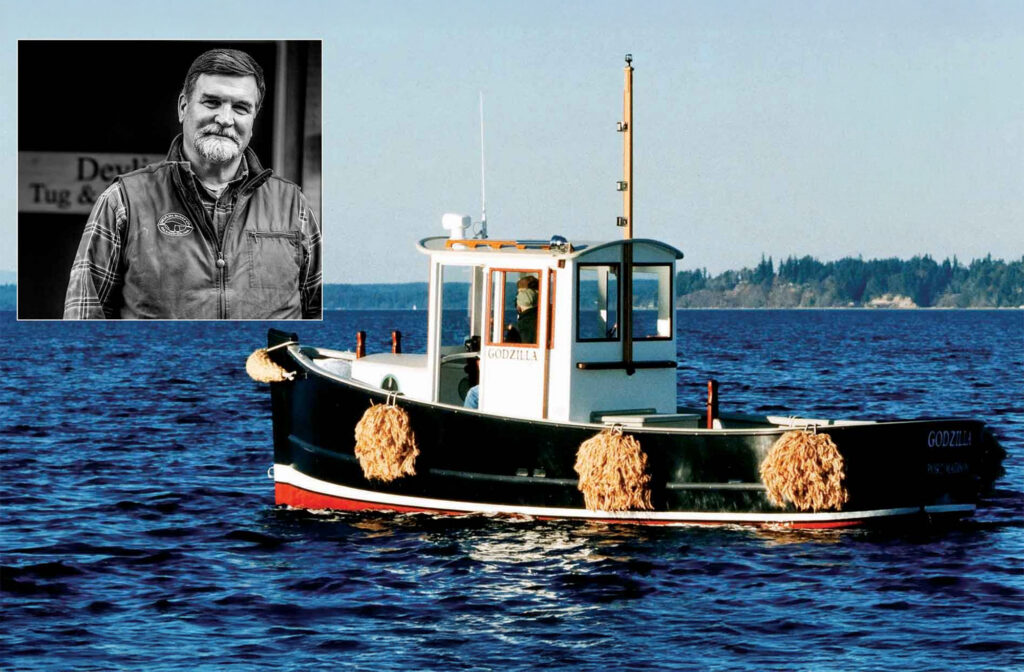

“I am currently in Flaming Gorge,” answers the fit, sporty-looking, clean-cut 34-year-old skipper from the cockpit of his current travel companion, a 22-foot Grady-White Seafarer. “It’s half in Utah, half in Wyoming, which I’d never even heard of before. People from my YouTube channel suggested it, and it is absolutely exceeding all of my expectations. It’s incredible here.”

For Gross, who has lived in minivans, an ambulance, a camper van, and even a converted school bus, the 22-foot Grady-White Seafarer, nameless with no home port—because she doesn’t technically have one—is just the latest vessel in a restless journey. Gross is not the kind of man who stays put for long. “You are quite the vagabond,” another interviewer teased him on a recent podcast. Gross laughed—a warm, easy sound that says he’s in on the joke.

Now, the vagabond is on the water.

Gross didn’t arrive at Flaming Gorge—or any of the other lakes on his ambitious list—by accident. His story begins in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a city defined by its three rivers and grit. “I grew up in Pittsburgh, and I was always boating from probably when I was 21 to 26, right before I started traveling full time in my school bus,” he explains.

For those five years, boating wasn’t just a pastime; it was a passion. The rivers gave him a taste of freedom, the kind that comes with the rumble of an engine underfoot and the shoreline slipping past. But then came a different kind of freedom: life on wheels. Gross bought a school bus, gutted it, and turned it into a rolling home. One bus led to another experiment—an ambulance, a camper van, even a minivan.

“I went almost 10 years without boating,” he admits, a note of disbelief in his voice, as though the decade away from the water was some kind of oversight. He filled those years with highways and horizons, sunsets over desert mesas, and the slow thrum of diesel and gasoline engines beneath him. But still, something was missing.

“After doing six or seven years of full-time traveling in a school bus and an ambulance and a minivan, I decided to head back to my hometown, bought a boat to live on full time while I was going to search around and actually find a house to live in,” he recalls. “And then I just continued making videos of living on a boat, and they started doing really well. So then I just kind of did a 180 and it was like the best of everything.”

Living small, living afloat—for Gross, the shift felt seamless. “It’s kind of like living in a small space in a bus and an ambulance is the same as living in a boat,” he says. “So it’s nothing new to me. I’m very comfortable with it.”

It wasn’t just comfort. It was coming home.

Gross’s first boat-as-home was a 2007 Cruisers Yachts 300 CX—roomy, twin-engined, and more spacious than any van or bus he had ever lived in. “It was the biggest boat I’ve ever owned, the first twin engine boat I’ve ever owned,” he explains. “And it was more spacious than my school bus and my ambulance by far. So I had so much space in there, it was amazing.”

The Cruisers was, however, a river boat at heart. Pittsburgh’s waterways were its natural habitat. When Gross packed up and aimed south toward Florida, a different kind of vessel was needed. He picked up a 24-foot Robalo, twin engines and all, with one specific dream in mind: “My goal was to get out to the Bahamas,” he says. “I knew that’s no safe or easy task, so I started from scratch. I knew nothing of what I was doing.”

That honesty—unvarnished, matter-of-fact—is part of his appeal. On YouTube, where bravado often rules the day, Gross’s humility feels almost radical, even if it’s hard to catch him in a shirt (he donned a casual t-shirt for our video call). “There’s so much hubris and machismo in boating every which way you look,” he said during our interview. “And here you are very methodically, in a very scholarly way, feeling your way through this on your own,” I commented.

Gross grinned at that. “That really means a lot,” he replied. “Because I think in this world, in pretty much all niches, there’s too much machismo. Whenever other people try to get into a new sport or a new activity, everyone else just shuts them down. And I see it all the time.”

The comments section of his early boating videos was proof enough. People doubted him, mocked him, sometimes outright scolded him. But instead of shrinking from it, Gross leaned in. “All of the merch that I created at first was literally just all of the mean comments that people left on my YouTube channel,” he laughs. “I just put ’em all on a t-shirt and started selling that because a lot of them I thought were just hilarious.”

If boating had taught him anything, it was to take himself lightly. “My mom always taught me to laugh at myself,” he says. “If I do something stupid, I laugh. I don’t care about it. I don’t get embarrassed. I roll with it, and I think that’s the best way to do it.”

The result? A boating channel that feels refreshingly human—and a community rooting for him as he goes.

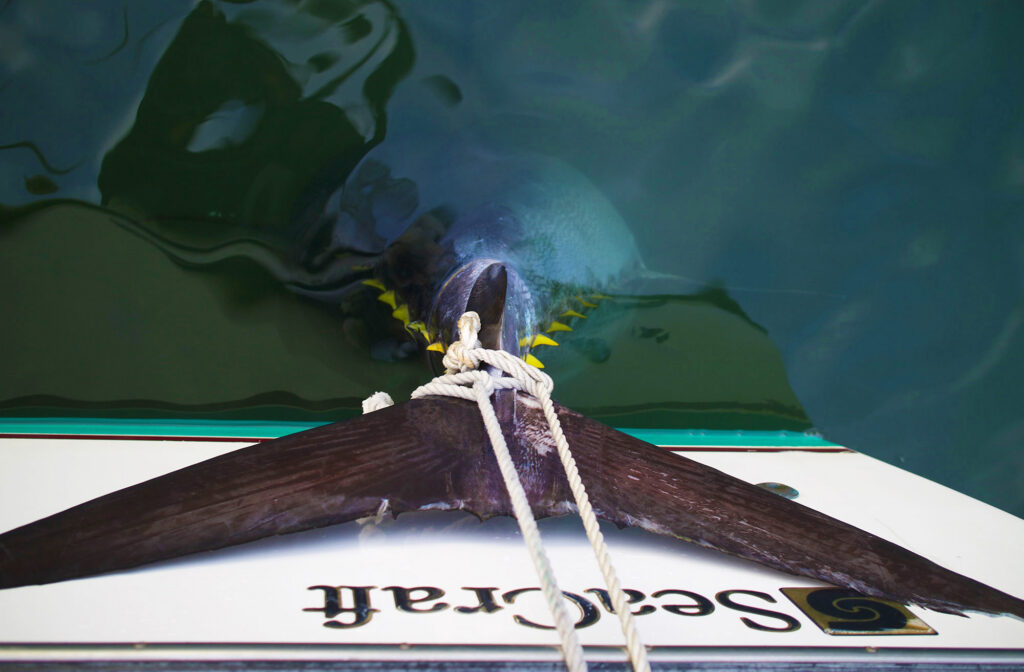

Gross’s 22-foot Seafarer is a capable little offshore boat more commonly seen chasing fish in the brine than trailering its way to mountain lakes. It wasn’t exactly what he had in mind—smaller was the plan—but, as so often happens in his story, the boat found him.

“One of my subscribers actually reached out and said, ‘Hey, I have this 22-foot Grady-White if you’re interested,’” he recalls. “So I drove five hours to this guy’s house and went out for a test drive in the most horrific weather in Florida, and then bought it from him on the spot, towed it five hours back, and here we are.”

Getting the Grady-White this far hasn’t been without incident. By his own count, he’s already trailered the boat more than 5,000 miles, winding from Florida highways to mountain switchbacks. He’s comfortable behind the wheel of a trailer— “I’ve done it since I was really young,” he shrugs—but even the confident tower can’t escape the occasional mishap.

In Tampa, his trailer brakes seized up on the highway. Smoke, red-hot drums, a friend driving behind who phoned him just in time: “He called me and was like, ‘Hey, man, it’s burning up back here. You gotta stop.’ So we stopped. Luckily they didn’t catch on fire.” The fix came quickly—a company overnighted him a new master cylinder—but it was a reminder that the road is as much a character in this story as the water.

Still, he takes it all in stride. “Knock on boat,” he grins, “I haven’t had any severe issues.”

The real cost of this cross-country odyssey has been, well, fuel. His 3.5-liter F-150 Lariat handles the weight fine, but “my fuel economy is absolutely horrific. It’s sad to see I’m getting eight miles to the gallon towing it,” he says, half-laughing.

But what the truck burns in gas, Gross makes up for in joy. He’s not checking every state off a list—this isn’t about completionism—but instead cherry-picking the lakes that truly stand out. “I kind of skipped over the Midwest,” he admits. “I feel like a lot of the lakes there are a little bit just flat and not the craziest scenery. So I kind of just passed that section.” Instead, his route arcs westward, toward rock walls and alpine water, toward Lake Powell, Tahoe, Mead, Havasu. “With the shortness of summer up north,” he says, “I really don’t have a huge window going far north.” So he calls audibles as he goes, adjusting the map like a sailor trims his sails.

Each stop is less about perfect execution than about discovery. Solo nights at deserted campsites. Learning the nuances of new waters. Waking to a Grady-White gently tugging its lines, ready for another launch.

And always, there’s the quiet astonishment of his own good fortune. “Without my following [that amounts to about a million between YouTube and Instagram as of September 2025], I would never be able to do what I’m doing right now,” he says. “I mean, I’m unbelievably grateful for this. There are so many times where I just take a moment and have a little elation moment, like, wow, this is really my life right now. This is what I get to do. This is incredible.”

For someone who has spent years rolling through the country in vans, buses, and ambulances, Brandon Gross sounds most at home now afloat—or at least close enough to it that a set of trailer wheels can pull him there. The boat, like the bus before it, is a vessel as much as a vehicle, a frame for experience more than a piece of gear.

And perhaps that’s why his audience feels invested in his wake. He’s not dangling the Bahamas or yacht-club prestige. He’s working out how to fix trailer brakes on the side of a Florida highway. He’s learning to cross waters he once thought too wide. He’s showing, in real time, what it means to start from scratch and keep going.

Looking ahead, the map is both vague and wide open. He’s recently booked it from Lake of the Ozarks—where other boaters asked, “Did you seriously trailer that thing from Florida to here?”—across to Flaming Gorge, a majestic, slithering reservoir spanning north-south between Wyoming and Utah, and straight across to Oregon, where he’s posted up with a friend and tending to some TLC of his trusty triplets: truck, boat, and trailer. From there, he’s considering cruising the Pacific Northwest for a bit if there’s time before fall sets in, but he’s primarily eyeing “at least a week” prowling his “favorite lake in the whole world,” Lake Powell.

Otherwise, he’ll choose routes by season, by scenery, or by a hunch from a follower’s comment. He doesn’t pretend to know exactly where it will all lead, but that’s the point. It also helps keep his “content” interesting. He had something of a following during his journeys through minivan, converted-ambulance, and converted-school-bus living, but the YouTube universe took a special liking to his sudden switch to boating.

For now, the Grady-White is his home, his content studio, his laboratory, his ticket west. Each morning is another ramp, another lake, another reminder that this country can still surprise you if you’re willing to let it.

This article originally appeared in the November 2025 issue of Power & Motoryacht magazine.