The Betty Jane II drifted slowly near the confluence of the St. Johns River and the Intracoastal Waterway, her idling 240-hp Yanmar the only discernible sound. A squadron of white pelicans huddled together on a shoal a polite distance away. Some porpoises surfaced nearby and seemed to express interest in us, then disappeared. Otherwise we were alone with nary another craft in sight. We had some thinking to do.

Our crew—Associate Editor Krista Karlson, Betty Jane’s master and commander, Deputy Editor Capt. Bill Pike and I—each studied a different type of cartography. Capt. Bill sat at the helm, looking at the Garmin chartplotter and then at our position through Betty Jane’s large windows. I stood behind him with NOAA paper chart in hand. Krista was at the settee paging through the Waterway Guide. “Nine feet, Bill,” I said, keeping an eye on the depth as he pondered both the plotter and our surroundings, looking concerned.

Krista confirmed our position by reading the buoy numbers with a pair of stabilizing binoculars—the guide jibed with the paper chart. We seemed to be in the right place, but could our nav aids be off? Storms have been known to shift buoys and even markers, and this area had seen its share of intense weather over the last year. We were in what appeared to be the channel, but our position on the chartplotter said otherwise. Betty Jane was dead in the water until we figured this out.

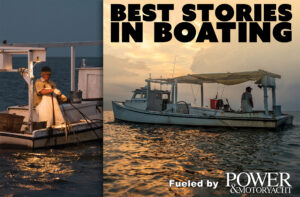

I went out to the cockpit for a breather. Wispy cirrus clouds hung high in the sky above, the mare’s tails indicating fair weather. Looking off to the north, I could just make out a craft that seemed to hover on the horizon. I concluded it was one of the large commercial vessels we had passed some time ago at an industrial quay closer to Jacksonville. I was wrong.

In an instant it was upon us, nothing short of a deus ex machina, an indisputable, incredibly well-timed appearance following the exact Greek translation—a god from a machine—in the form of a 65-foot Huckins. Both Krista and Capt. Bill saw the vessel as well, approaching at a good turn of speed. “They seem to know where they’re going,” Capt. Bill remarked.

When the boat had passed, we radioed over, and the captain took only a split second to reply. “Your Garmin cartography is off. Keep goin’ the way you’re headed, and you’ll be okay.” Our apparent unfathomable difficulty was immediately solved. We thanked him and with that, the Huckins was back on plane and we continued down the ICW. Mythology would define our time together, as our trip seemed influenced by the Greek Gods.

It had started earlier that morning. I studied the starry sky over the Ortega River as we prepared to load up Capt. Bill’s handsome, 28-foot Cape Dory; I was looking for the Dioscuri. When embarking on a pre-dawn voyage I always attempt to locate the constellation Gemini—its brightest stars, half-brother twins Castor and Pollux are the patrons of sailors—to silently call upon them, seeking fair winds. According to Greek mythology the brothers also had a knack for materializing at the moment of crisis, helping those who honor them avoid calamity. Betty Jane’s crew would be fortunate to meet what I’d qualify as brothers in arms on either side of the bascule bridges that served as bookends of our voyage.

The first of those ‘twins’ was Capt. Bill’s friend Jerry. He looked like a giant from where I stood in Betty’s cockpit. The burly, former state trooper and one-time bodyguard to a governor was the friendly face we needed as the sun rose over Jacksonville’s Marina Mile. Immediately, Jerry began helping Krista and I load up while politely chatting about the trip we were slated to embark upon. He eased the tension of coming on board with our gear via a rail-thin finger pier, an easy way to end up in the drink with a 40-pound pack on your back. He complimented Betty’s restoration as Capt. Bill checked the engine’s vitals while suggesting he’d join us if we needed an extra hand, like the Dioscuri who enlisted as crew of the fabled Argo in search of the Golden Fleece. After all, we were headed to the land of the Fountain of Youth.

Our journey started in earnest after we cleared the Ortega River bascule and made our way generally eastward upon the St. Johns, the Sunshine State’s longest river and one of the few in the United States that flows north. Once we cleared the marked no-wake and manatee zones, I expected Capt. Bill to drop the hammer and briskly leave Jacksonville in our wake.

Well, the Yanmar 4LHA-STP hummed along at the optimal 2500 rpm at a more leisurely pace than I was used to—with an unfavorable tide, we averaged about eight knots. Could I do this for nine hours? Maybe the old mariner will want to see Betty hop to it and firewall the throttle? I thought to myself. Alas, double-digit speeds were not in the cards.

Slowly, we began to leave the urbanized section of the city behind. Just west of Mayport, a little past where we saw the Baltimore-built research and recovery ship Atlantis II that was part of the 1986 Titanic expedition, I turned to my companions and began to revel in our slow adventure.

The three of us huddled together on the flybridge’s bench seat, exchanging stories about our lives that we hadn’t found time to talk about at boat shows and other salty events. Both Krista and Capt. Bill have seen a lot of the planet—she as a continent-hopping backpacker and Capt. Bill first as a skilled commercial captain, then as a daring marine journalist. We freely shared stories as the shoreline transitioned from gorgeous homes with giant docks to desolate stretches of estuaries dotted with sand live oak, saw palmetto, sabal palm and just about every type of marine bird. When we finally entered Matanzas Bay, with St. Augustine’s Castillo de San Marcos National Monument off our starboard quarter, we were right on schedule for the Bridge of Lions bascule to allow us to enter our nation’s oldest city.

After refueling and getting Betty organized in her slip, we set off on land. “I feel like we’re in another country,” Krista said as we walked through an intersection flanked by the Lightner Museum and the Ponce de Leon Hotel. Both structures are stunning masterpieces of late-1800s Spanish Revival architecture, with the latter serving as the hub for Flagler College, the school’s namesake taken from Gilded Age industrialist Henry Morrison Flagler. This feeling would continue along the town’s narrow cobblestone roads, many lined with live oaks dripping in Spanish moss.

We use trips like these not only to bond as a team but also to put marine gear to the test in real-world environs. Krista had shipped down a slew of items, including a neat little electric bike that folds up to fit in a suitcase. We had our terra firma—but we were missing one key component.

“Guys, this is my fault. I left the dang bike seat in a five-gallon bucket in the back of my car,” Capt. Bill lamented. We decided that I’d somehow find us a seat, so off I went with an idea to apologize for borrowing rather than asking for permission to temporarily liberate a saddle for my crew.

Sometimes, it seems like I’m gathering material for future works of fiction. I figured I’d have to apply the skill, daring and resourcefulness that Capt. Bill used while guiding 800-foot tug-and-barge combos up and down the Houston Ship Channel all those years ago. But then I met Thor (yes, that is his real name), the other half of the Discouri brothers.

Thor rented scooters and other oddball wheeled contraptions out of a converted gas station just west of the university. “The Greyhound station is that way,” he said, mistakenly thinking my suitcase held my possessions instead of a bike. I explained our predicament and within five minutes, I had a seat installed and Thor was charging the bike’s battery. “This thing’s pretty neat,” he said as he accelerated at a good turn of speed, slaloming through the lot with the causal, nonchalant manner of a former professional skateboarder.

We filled our remaining time together as landlubbers and tourists, from the Fountain of Youth site (underwhelming) to the Cathedral Basilica (gorgeous and under restoration) and the Castillo de San Marcos (closed due to the government shutdown). On our last morning, Krista and I sat in an espresso bar and watched our very own marine matinee idol, Capt. Bill exchange pleasantries in the Plaza de la Constitución with yet another fan who recognized him from the magazine, the second such encounter in as many days.

It would happen again on the ICW on our way back north, when a passing Grand Banks radioed over to express admiration for the Betty Jane II and for its head of restoration. It helped Capt. Bill somewhat recover from his battle with Charybdis, the ripping current and whirlpools that had kept him awake the previous night.

When we finally reached the Ortega River Bridge, satiated from the healthy-ish cornucopia of hummus, olives, peanut butter, pita, crackers, almonds, a basic charcuterie and assorted candy, we had to wait for the sun to drop below the horizon so we could see Capt. Bill’s quay. Jerry was there to greet us, giving us a hand with the lines. I was reminded that the stars are always out, their latent presence ready to guide us to safe harbor even when we can’t see them.

Read Capt. Bill Pike’s take on the trip here. ▶