Family Heirloom

Loafer is only 26 feet long, but she makes a big and immediate impression. So does her caretaker of more than 30 years.

Among the fiberglass hulls that fill the slips at Port Niantic Marina in East Lyme, Connecticut, is an odd ship. Loafer is only 26 feet long, but she makes a big and immediate impression. She is the last -remaining wooden vessel at the marina, and she is cared for by an equally memorable woman.

Judy Healy is Loafer’s keeper. She grew up on the boat with her family, and she now single-handedly tends to all of the boat’s needs. She has made it her mission to protect and document every known -aspect of the little boat’s past.

Loafer herself is a cute, albeit simple, little ship. Her aft deck has a bench and a fold-down table, and her cabin has two bunks and a forward head. The interior is filled with nautical trinkets and sea-inspired dolls that Healy has hand-sewn. An antique vessel, Loafer has a top speed of 4.8 knots and usually cruises at 3.5 to 4 knots. Healy doesn’t need more power. She likes Loafer just as the boat is.

Healy has spent every summer on Loafer since she was born in 1949. The boat has been in the family since her father purchased her in 1940 from the Marion Motorboat Club.

“We’ve never missed a year on the water since 1940,” she says. “My father and his friend thought they would buy a boat, and they paid $125 each for it. It broke both of their bank accounts, and my father got into the car and said to Joe, ‘Oh God, what did we do?’”

Her father was an electrician by profession and felt a bit out of his element in taking on such an old craft. Still, he and the man Healy calls “Uncle Joe” got to work on a restoration that has kept the vessel seaworthy to this day. The boat was originally built light and lacked the critical framework, so the men added floor timbers to the bottom to hold the planks and frame to the keel.

“He said that’s what probably held it together,” Healy says. “A lot of these boats were made very cheaply because they were in the transition from sail to power.”

She knows little about Loafer’s history aside from the initial construction, although she suspects the boat was built around 1900. A circular piece of wood on the cabin ceiling indicates that there was once a smokestack and a coal stove on board, but those were gone before her father purchased the boat. He knew that it was not a commercial lobster boat because it did not have the wide sides for pots, so his best guess was that the boat was designed as a fishing vessel that could store a week’s provisions for two men.

Her father initially used Loafer to patrol the Connecticut River and the Thames River for enemy vessels as a temporary member of the U.S. Coast Guard Reserve during World War II. After 1945, he used the craft as a pleasure boat, often taking her fishing at Bloody Ground south of Millstone, Connecticut, and at Old Silas Rock in New York. During that time, the boat became permanently intertwined with the family. Healy’s father had his first date with her mother on board, and when Healy was born in 1949, Loafer permanently transitioned into a family boat.

She fondly recalls spending every summer weekend aboard with her parents. Often, the three of them would take the craft to her father’s favorite fishing destinations, and she and her mother would relax while her father fished. He was still involved with Loafer’s care until he died in 1990. Now, the boat is Healy’s project and passion. Her scrapbooks document every restoration and every adventure the boat has taken with her family.

Healy remembers the bygone days when everyone at the marina knew one another and spent the entire summer on their boats, so even if she doesn’t take Loafer out of her slip, she is content to sleep on board each summer weekend. As the boat does not have steerage in reverse, docking is hard, and Healy prefers to do it with another person aboard.

She took the boat to the Mystic Antique & Classic Boat Rendezvous from 1996 to 2002, but she has since retired from making the trip. She also attended OpSail in New York in 2000 and 2012. Now, she primarily takes Loafer on local cruises around Niantic’s bay and river with friends and family.

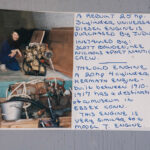

Scott Bowden, manager at Port Niantic Marina, met Healy’s father 31 years ago, when Bowden was called to review an engine problem on the boat. He met Healy shortly after, and she has been his customer ever since. Bowden helped the family find a replacement engine for the boat’s original Kermath, which took close to five years. The replacement engine is a Universal Diesel.

“It’s a big part of her life, that boat,” Bowden says. “She’s one person in the boating community that deserves to be applauded for staying with it over the years.”

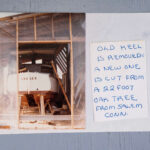

Keeping such an old wooden boat seaworthy requires unwavering dedication to its structure. The first major restoration was in 1983 by Bert Smith, a shipwright at Port Niantic before all the wooden boats disappeared from the water. He started working on Loafer when the keel was falling out. The entire bottom of the boat was removed that winter, and she was back in the water by summer. In 2016, Bowden introduced Healy to Keith Chmura, a private shipwright, and he has since been in charge of the woodwork.

“We try to pick things to restore that we can get done in one season so we don’t have the boat out of the water,” Chmura says. “Usually at some point a boat that age sits out for years and dries right out, but it has been in the water every single year for so long, and that is part of the reason it has lasted.”

One of his largest restorations to the boat was adding a plywood and fiberglass deck to stop leaks. He also rebuilt all of the windows and added an aft deck. He is working on replacing planks on the bottom for the third year in a row.

Chmura says Loafer’s round-bottom, full keel hull is built similarly to that of small sailboats. He thinks the boat may have even had a sail at one time. “Engines were relatively new then, and a lot of boats had sails on them because they didn’t trust the engines yet,” he says.

While the hull design is not overly complicated, it is challenging to work on a boat of this age. Healy approaches the task differently than other owners. “A lot of these projects end up building a new boat and saying it’s the same one,” Chmura says. “That’s not what this project was about. She has a very strong bond with this boat. She doesn’t want a new boat.”

He adds that he has to be careful to never take apart too much at once, because he would not be able to put it back together with the same wood. Luckily, Loafer is small enough that he doesn’t have to pull out the internal structure to get to any part of the boat.

Loafer’s restorations are not cheap, and Healy works 50 hours a week on top of her job as a seamstress to pay for the repairs. She has also put her seamstress expertise to work on board, designing and sewing all the upholstery in the cabin and the canvas cover on the aft deck.

And although Loafer keeps Healy connected to her late parents, the boat has become the object of her affection independent from them, as well. The love affair came full circle when she was married on board, right where her parents’ relationship blossomed. She planned a 1900-themed reception in honor of Loafer’s suspected year of construction, and Bowden made an appearance dressed as a sea captain from the era.

Wooden hulls have all but disappeared from the water, but Loafer persists. She may require more upkeep than a fiberglass hull, and she certainly takes her time while cruising, but as the people who love her know all too well, no modern build can match her character.