Oh Spare Me!

Some folks carry almost enough spare parts to rebuild their boats.

But really, you don’t need much—not like in the old days.

In my early 20s, I rode a BSA motorcycle, a 650-cc Thunderbolt. If you’ve spent time straddling a classic British bike, you know the importance of carrying spare parts, and maybe spares for the spares, whenever and wherever you ride. Boats were the same way back then, in the “good old days”: If you didn’t break down at least once every weekend, you weren’t using your boat. You carried an array of V-belts, impellers, spark plugs, points and condensers, carburetor cleaner, fuel filters, random lengths of wire, a box full of odd nuts and bolts—all sorts of things. And diesels were not immune: For years, I kept a spare set of injectors and a head gasket in a drawer under my berth although, thank goodness, I never had to use either.

That was then, though; today, boats are dependable critters, especially if you keep up with your maintenance. But some skippers still haul such a cargo of spare parts around that there’s barely room left over for the crew. And I’ll be darned if I can figure out why. After all, most of us spend the majority of our cruising days not far from shore and within easy reach of assistance, even if we’re voyaging far from homeport. Indeed, cruising today is sort of like taking a road trip: Although you’re a long way from home, AAA is usually nearby. So, unless your boat is the seagoing equivalent of my 1972 Beezer, I think you can safely leave the marina with only a few basic parts and tools. And hey, sometimes maybe you can cut back to just a towing-service account and a credit card. Let the seagull hit the fan. You’ll simply arrive at the boatyard at the end of a towline. Ignominious, but it beats attempting complex repairs at sea.

The One “Spare” Everybody Needs

But first, let’s get real. Certainly, you should carry enough parts and tools to handle simple glitches, stuff that’ll handle the seagoing equivalent of changing a flat tire. You don’t always want to wait for Sea Tow or TowboatUS. And since all boats are different, there’s no general rule governing what you should have onboard, no “Carry three model XYZ fuel filters and an extra ship’s cat,” for example. So for specific engine spares, ask your mechanic. However, although it’s not technically a “spare” perhaps, the one thing every boater should always carry is an anchor at the ready. When your engine dies, the first thing you should ask yourself, in the deafening silence, is, “How about that anchor!” If the problem’s one you can deal with, it’ll be a lot easier to focus on it if you’re not worried about drifting ashore or into traffic. If you’re calling for a tow, why not minimize your drift while waiting? Dropping the hook in an iffy situation is like putting out safety reflectors before changing a tire alongside the highway. I always carry two anchors of different patterns, by the way, to handle a wider variety of bottom conditions. And, now that I think of it, some people do refer to that second hook as a “spare,” at least sometimes.

The Other Spare Everybody Needs

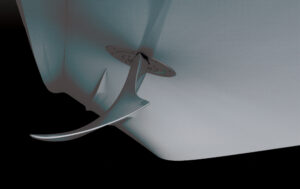

Let’s face it. You also need to always carry a spare impeller for each and every raw-water pump onboard. A plastic bag or other obstruction in the seawater supply can make an engine overheat in minutes, overheating can damage the impeller, and a damaged impeller can break apart and scatter bits of rubber throughout the seawater cooling system. Then you, or a bunch of boat yard guys, have to ultimately and laboriously hunt them down.

Replacement isn’t a terribly tough job. Once you’ve removed the faceplate from the body of a suspect raw-water pump, inspect the impeller inside carefully. Look for cracks at the base of the vanes or damage at their tips. If you see trouble spots or you’re in doubt, swap the darn thing out. Impellers, after all, don’t cost much, compared to mechanics. And of course, as soon as possible, buy another impeller to replace the spare you’ve just made use of.

And maybe check out Speedseal (www.speedseal.com) as well, if you haven’t already. This cool little company makes faceplates that substitute big hard-to-drop thumbscrews for regular screws. If you’ve ever plunked one of the latter little devils into the bilge while fiddling with a screwdriver, you’ll appreciate this. By comparison, Speedseal thumbscrews can be tightened or loosened using just your fingers. You can buy a pack of spares for a few bucks, too. And the faceplate seals with an O-ring, so there are no paper gaskets to fool with.

And one last thing. If frequent overheating is a problem in your area, thanks to seaweed or junk in the water, why not switch out your standard impeller for one that can withstand running dry for longer periods, like one of the self-lubricating Run-Dry impellers from Globe Composites (www.gcsmarine.com)? The manufacturer claims the Run-Dry can run dry for up to 15 minutes (that’s about twice as long as a conventional neoprene impeller) before self-destructing, and they claim it also has a higher tolerance for sand, grit, and other contaminants. Installing such an impeller should give you plenty of time to notice an overheating issue and shut down your engine before it starts to cook.

Don’t Ignore Your Fluids

I once was the shipmate of a diesel that tended to unscrew the petcock that drained its freshwater cooling system, transferring coolant into the bilge. For safety’s sake, I always carried enough extra coolant to refill the system twice. While that’s probably more than you’ll need, you should have enough coolant onboard to top-up without having to dilute with water. Experience will tell you exactly how much, since it depends on your engine’s capacity. You might go years and never need a drop, but, on the other hand, your engine might turn on you like mine did and dump all its coolant in one afternoon. (Yes, I eventually replaced the petcock with a plug. Problem solved.)

Got time for a short sermon? The day you sail without spare elements for your fuel filters is the day the sea rises and churns up blooms of sediment in your fuel tanks, clogging the fuel system. The moral? Always carry spare elements. And have a sealable container for draining the primary filters into, so fuel doesn’t end up in the bilge. If your diesel requires bleeding after fuel starvation, keep the necessary tools in one convenient, easy-to-get-to spot. When you’re trying to restart an engine under less than ideal conditions, you don’t want to be rummaging around in your toolbox for wrenches.

And always carry spare oil—lube, transmission, etc.—and oil filters. When an unexpected leak occurs, a couple of extra quarts can often get you home without calling for help. And if oil has somehow found its way into the bilge, shut off the bilge pump so you don’t pollute.

If you’re planning an extended voyage, you’ll of course want more spares than the few I’ve just listed. The long-haul list should probably include a repair kit for your pressure-water system and another for the head (which I hope you never have to use), as well as zincs for the heat exchangers. I’d also recommend adding a spare prop or a set of them, in case you wrap one up while exploring some isolated anchorage. If you’ve owned your boat for a while, you’ll know what systems are most vulnerable; if not, work up a complete spares list with your mechanic.

In any case, you can’t argue with the fact that times have changed. Today, instead of a temperamental BSA, my ride is a Prius, which I couldn’t repair if my life depended on it. So the only spares I carry onboard while cruising terrestrially are a tire-repair kit and a 12-volt air pump. Anything else—I call a tow truck. I think the approach works pretty well for boating these days, too, since boats are so reliable and towing companies so plentiful. Hey, think of all the money you’ll save on parts you’ll never use and the tools you won’t need to install them.

Pull Your Impellers

Impellers work better and last longer when they’re used regularly and indeed they suffer from sitting idle in pumps for long periods, like over the winter. The vanes take a “set” and don’t pump as well come spring. (If your impeller already has a set, the folks at ITT Jabsco say to flip it around so it rotates in the opposite direction.) To prolong the life of their impellers, many skippers pull them out of the pumps at haul-out time and reinstall them in the spring. (Old-timers recommend tying the ignition key to the impeller so you don’t forget.)

Pulling an impeller gives you a chance to inspect its condition, too. The wear pattern on the vanes indicates problems with the pump and its plumbing. And what’s more, since most experts suggest replacing impellers after 200 hours of operation, it’s probably smarter to go with new instead of old come springtime. In fact, why not, as a rule, start the season off with a fresh impeller in your powerplant every year? That impeller is an important component, one that’s way more vital than its modest cost would indicate. Installing a newbie is a job you can perform yourself with just a few tools and a modicum of mechanical skill. Doing it dockside, at your leisure, will help if you ever have to replace one at sea. And the project will alert you to any idiosyncrasies of your boat that might make the whole procedure more complicated than you expect.