From a Boatyard With Love

The yard can make or break your yacht-owning experience, so choose wisely. Here’s some advice to avoid heartbreak.

At a boat show many years ago, I overheard two executives from a major boatbuilder, one whose boats you’d probably like to own, lament the loss of first-time yacht buyers because of bad experiences with boatyards. Builders rely on buyers moving up into larger boats to keep solvent, and if an owner has a bad boatyard experience right off the bat, not only will they not move up, but they’re likely to sell the boat and take up another sport. Did I hear someone yell “Fore”?

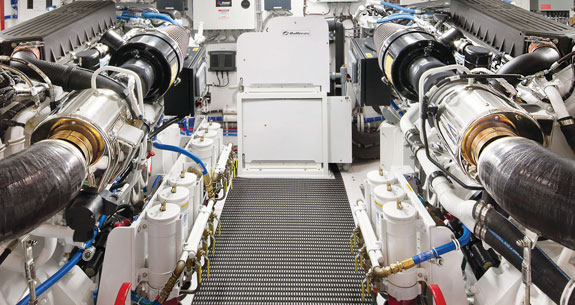

It’s no secret that boats require lots of maintenance and repairs, and with builders piling more stuff onto even small-ish vessels, the situation is getting worse, at least from a technical standpoint. -Keeping the mechanicals, electronics, plumbing and so forth -working as designed, while also maintaining the vessel cosmetically, means writing checks, often for large amounts, on a regular basis. But that’s okay: It’s the cost of having fun, and you expected it when you bought the boat, right?

What’s not okay, however, is handing over bags of money for a job well done when it isn’t, forcing an impasse with the boatyard—in the worst case, while your boat sits crippled and unusable. Suddenly “fun” becomes an unpleasant, sometimes litigious, chore. I’ve been there, as both a captain and a boat owner, and it’s not a good place, although I’ve never been tempted to buy a set of Callaways and a pair of spiked shoes. A bad yard experience shouldn’t make you give up boating: Busting free from a lousy yard isn’t as risky as taking a midnight swim from Alcatraz, or as expensive as dumping that -Vegas showgirl you met at the last technology convention. All it takes is common sense and due diligence.

Avoid “Colorful” Yards

Nobody likes mooching around funky boatyards more than I do, investigating the always-present fleet of abandoned boats—most of them fiberglass sailboats from the 1960s and 70s—and maybe -finding something interesting in the marine junk that’s strewn around. If you’ve got an old boat that you’re restoring as a long-term project, maybe this is the kind of yard you want, a place that’s pretty forgiving of do-it-yourselfers. There are usually a bunch of grizzled old-timers hanging around who are interesting to chat with and can sometimes clue you in on how things were done way back when your old boat was new.

But if you own a modern boat with complex systems that require specialized know-how to maintain and repair, and you don’t want to provide on-the-job training to the yard crew, steer clear of the colorful boatyard. Find a clean yard with trained technicians, well-maintained equipment and a service-oriented management team interested in keeping you as a customer. Step one is to search online; Google “boatyards [your state]” and spend time on the websites of any yards that look promising. The site should be informative and up to date, listing the yard’s facilities and capabilities along with the hourly rates for various jobs; most have downloadable work -orders, too. A website is the most basic of marketing tools, so if a yard doesn’t have one, or doesn’t keep it updated, are they seriously in business, or just waiting for a developer to buy their very valuable waterfront property? (Seems like there are fewer colorful yards on the waterfront today, so maybe most proprietors have opted for that golden buyout.)

There’s also the American Boat Builders and Repairers Association (ABBRA), an industry organization with more than 250 members, mostly boatyards. Membership fees aren’t onerous, $525 per year for yards with more than 20 employees, so there’s no reason for a yard not to join. There are benefits in being an ABBRA member—insurance deals, training programs, and the chance to win the Boat Builder or Boatyard of the Year award. Members agree to abide by a code of ethics, which basically says they won’t cheat customers, something cynics might argue is only as good as the person doing the -agreeing. But there’s a member directory on the website, and I find lots of yards on there that I know are reputable and not many that suggest colorful. From the directory, you can click through to each yard’s website, which will streamline your research. I often need to talk to qualified boatyard folks when preparing this column, and I always start by checking with ABBRA. It’ll work for you, too.

Check the Certificates

Find a yard that’s authorized to repair and maintain the systems you have on your boat. Any boatyard worth its valuable waterfront -acreage will employ technicians with up-to-date factory training in engines and marine systems. It’s an investment in a quality workforce that a decent yard will make, and one that could save you -money and time when your boat needs TLC. Most yards list their manufacturer authorizations on the website; if not, call them and ask. You wouldn’t take your Tesla to a Volkswagen mechanic, so don’t expect a MerCruiser-trained tech to fix your CAT diesel. Check first.

The American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) certifies technicians in a number of disciplines, from general knowledge of ABYC Standards (something any marine tech should know) to gasoline and diesel engines, air conditioning and refrigeration, corrosion, composites and so forth. To earn certification, the technician has to prove two years of work experience, complete a certification course and pass a comprehensive exam; there’s also a healthy fee involved, usually close to four figures, so only techs serious about their work will spend the money and time. The certification is good for five years. The individual is certified, not his or her employer; some certified techs run their own businesses, but many work for boatyards. You’ll find a list on the ABYC website; look under the resources heading. Each certified tech is listed, along with his/her affiliation—Such-and-Such Boatyard, for example. It takes some clicking, but you can ascertain what yards in your area have certified techs on their crews.

And don’t forget word-of-mouth, often the best “certification” there is. Hang around the marinas on weekends, and ask folks who have similar boats to yours for recommendations. (Share your boatyard horror stories, too—it’s cathartic.) More boat owners will -complain about yards than compliment them, so if one yard gets frequent recommendations from the man-on-the-dock, it’s probably a pretty good one. Ignore anything sailboat owners tell you: They complain about everything and are never happy. I’m not kidding. Sailboat engines and systems are seldom easily accessible, so both maintenance and repairs take longer, and cost more, than similar projects in the powerboat world. Big yard bills, after all, do not a happy camper make.

You Don’t Need It All

Don’t look for too much boatyard: Unless you own a megayacht, you don’t need a yard with a TraveLift that can hoist the Great Pyramid. You rarely need a yard with a paint bay—you won’t need to paint your boat until it’s at least 10 years old, longer if you take care of the gelcoat. When it’s time for an Awlgrip job, find a yard that specializes in that skill; 10 years later, return for a re-coat. Don’t discount an otherwise acceptable yard because it doesn’t have things you’ll rarely need. Mostly, you need a good engine mechanic and a tech who can keep your air conditioning operational.

Move between yards to make the most of each one’s specialties, especially if undertaking a major repair or upgrade project. The best yard might be a couple hundred miles up or down the coast, but if you’re spending thousands of dollars, or more, it’s worth the trip to get the best bang for your boatyard buck. And, need I say it, find a yard that services boats that are similar to yours. Techs get used to working on certain kinds of boats—if you have a 70-foot sportfisherman, find a yard full of big sportfisherman, not mid-sized express cruisers or outboard-powered center consoles. You, and the yard crew, will be happier.

Follow these tips and use common sense, and your boatyard -experience should be a happy one—expensive, but happy nevertheless. And next year you won’t find yourself browsing in the pro shop for a new putter or a pair of plaid plus-fours.

Be a Good Customer

Once you find a good boatyard, make yourself a valued customer. Even if it’s a DIY-friendly place, don’t do everything yourself; give the yard some work. Taking up space in the storage lot doesn’t turn a profit for the yard, and boatyards aren’t that lucrative at best. The margins are much lower than you’d think, especially considering the hourly rates any decent yard will charge. But there are lots of expenses, myriad laws and regulations that are costly to follow, high insurance rates and the constant threat of steep fines for violation of any environmental taboos.

Hold up your end of the bargain by hiring the yard to paint your bottom, compound and wax the topsides, or give your engines their spring tune-ups. The yard crew can do most jobs better, and faster, than you can anyway, and do you really want to spend your leisure time crawling under your boat with a paint roller dripping antifouling? Not me—I’ll pay the boatyard piper, and promptly: Never make the yard send you a second bill. Then, when you need work done ASAP at the height of the season, they’ll be more amenable to helping out.

And don’t forget to tip the yard crew. Yeah, I know you’re paying $70, $80, maybe $100 an hour for their time, but that doesn’t trickle down to the folks who actually do the work. Tossing a few $20s around now and then will return more in value to you than the cash it costs.