Stabilizer T.L.C.

Want to keep your stabilizers happy next season?

Here’s what you need to do now.

Maybe your present boat doesn’t have stabilizers, but chances are your next one will: Like bow thrusters, both mechanical and gyro stabilizer systems have shrunk enough these days to be feasible for boats from 35-some-feet and up. If you’ve ever endured a rolling, open-sea passage in a midsize trawler yacht, you’ll welcome this news. But what does it take to keep a set of mechanical stabilizers (I’ll cover the gyro-types in an upcoming column) functioning? Will repairs and maintenance tip you off your rocker? What should you do now to keep your fins finning happily next season?

Because of the size and weight of many fins, it’s generally a good idea to get help from the boatyard crew to maintain a stabilizer system.

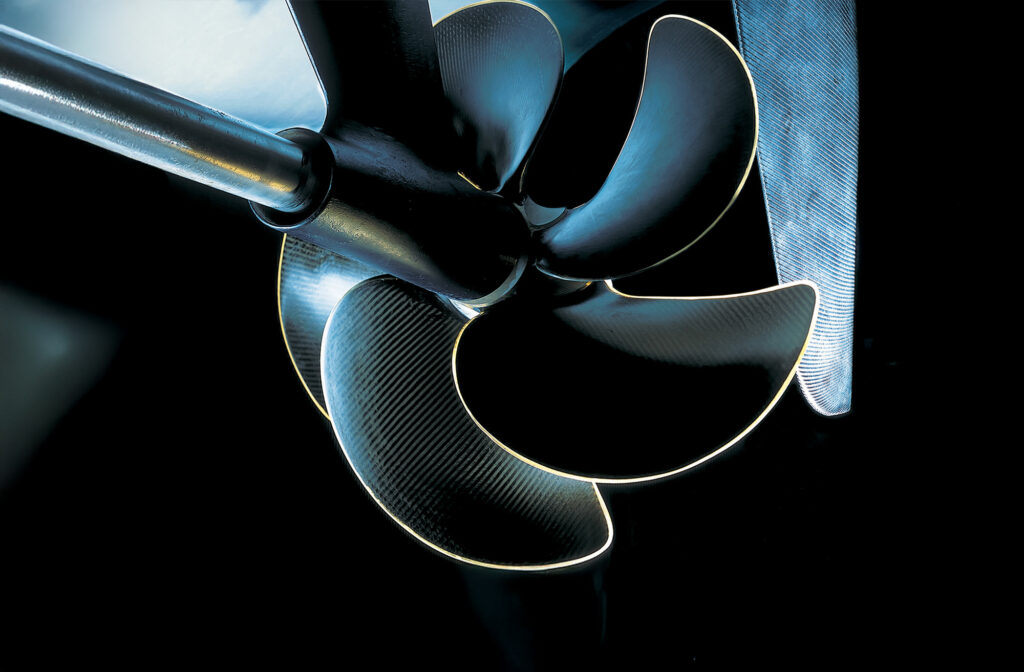

Most mechanical stabilizer systems today use fins on either side of the vessel to create forces opposite to the direction of roll, thereby damping it. Certain mechanical stabilizers use technology other than underwater fins, however—Quantum’s MagLift system (www.quantumhydraulic.com), for one, employs spinning cylinders that create lift thanks to the so-called Magnus effect, the same phenomenon that affects the flight path of a spinning tennis ball. Some mechanical stabilizers work at rest as well as underway—they often need a bit more maintenance—but in any case, in anything but a flat calm, virtually any mechanical stabilizer system is in constant motion. The fins, cylinders, or whatever, move endlessly to keep the hull level, directed by an array of motion sensors, speed sensors, position sensors, servo valves, and other cool stuff linked together through a sophisticated control box.

Most of these types of stabilizers are engineered to require minimal day-to-day maintenance. It’s not much different from what your engines demand: Fluid levels and pressures need checking, moving parts need greasing, hoses or oil seals can leak, oil filters periodically need replacing, cooling water needs to keep flowing. But occasionally more complex services are necessary, some requiring that the boat be hauled—for these, now might be the time.

Stick to the Schedule

Where do you start? First, cross-reference the maintenance schedule included in your stabilizer operating manual with your ship’s maintenance and cruising logs. Manufacturers generally provide both service hours and real-time intervals for each item, from the most mundane to the complex. Schedules vary from one manufacturer to another: Naiad (www.naiad.com), for example, says to change the fin shaft seals at least every three years or 4,000 hours of use, more often if the stabilizers aren’t used at least twice a month. American Bow Thruster (www.thrusters.com) wants you to do the same on their TRAC stabilizers at least every six years; Side Power (www.imtra.com) stipulates seal changes every 12,000 hours (which represents about 3 years of heavy use, according to Side Power); Quantum says every five years or 8,000 hours.

Other major maintenance procedures have similarly long intervals, but all can be involved and costly: For example, shaft seals are easy to replace, but the hard/expensive part is dropping the fins first; you’ll need a trained technician with the right equipment, and the yard’s help for all but the smallest fins. Some fins are attached to the shafts with bolts or other fastenings, and are straightforward to remove. Naiad, on the other hand, uses a different method: The tapered, splined fin shaft fits into a tapered bore in the fin, explained company technician Charlie Egan; it’s a pressed-on fit with no fastenings. Removing the fin demands special equipment: a hydraulic tool to pop the two pieces apart for larger fins, a mechanical puller for smaller ones. Both cases require a skilled technician to do the job.

Voice of Experience

“The systems are pretty much bulletproof,” said Capt. Carl Gwinn, who has been shipmates with stabilizers for many of his 30-plus years of professional service on motoryachts up to 180 feet. “But stick to the service intervals.” Holder of a U.S. Coast Guard 1,600-ton license, Gwinn is currently the captain of a Nordhavn 86 home-ported on the East Coast. The owners of the Nordhavn are serious cruisers, so her TRAC Digital stabilizers get a good workout every year. Capt. Gwinn explained that stabilizer maintenance starts with common sense. Look for leaks regularly, and if you hear squeaks or unfamiliar noises, check them out.

“Many people neglect the [hydraulic oil in the] cooling system,” Gwinn continued. “You have to keep it clean and functional or the oil gets hot, very hot, so hot you can’t touch the tank.” Indeed, the oil can get hot enough to change the color of the paint on the hydraulic oil reservoir, he added, or even make it bubble. Overheated oil causes other problems besides burned paint, so take steps to ensure your cooling system keeps working properly. Change the raw-water impellers on schedule, check the zincs, and open and inspect the heat exchanger if you suspect problems. Treat your stabilizer system like you do the heat exchangers on your engines, advised Capt. Gwinn, and check the oil temperature regularly.

Photo Credit: Nordhavn

Many long-range cruisers like this Nordhavn rely on active stabilizers to keep things steady offshore. Other skippers stick to reliable, low-tech paravanes.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Capt. Carl Gwinn

Stabilizer fins are big and heavy on large yachts.

Here, it takes three guys and a forklift to replace the fin after removing it for service.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Nordhavn

Fins work best when they’re tight against the hull throughout their rotation.

Water escaping between the top of the fin and the hull adds drag, reduces efficiency.

Here, a section of the round bottom has been flattened to accommodate the fin.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Nordhavn

Winglets (maybe we should call them “finlets”) at the tip of the fin reduce turbulence and drag by preventing water on the high pressure side from swirling around to the low pressure side.

Racing sailboats use the same technique on their keels, and airplanes on wingtips. Note also the guard to keep weed and other debris from getting jammed between fin and hull.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Nordhavn

The mechanism inside the hull requires little day-to-day maintenance, mostly checking fluid level before start-up, and monitoring oil temperature and pressure during operation.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Nordhavn

The oil cooler at the left of this photo — the tube marked HOT — can get very hot indeed if the flow of cooling water is blocked, so hot it can make the paint bubble. Overheated oil has to be changed, so keep an eye on both cooling-water flow and the oil-temp gauge.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Naiad

Naiad stabilizer fins press onto the shaft, rather than the typical set-up of the shaft being permanently attached to the fin. The shaft seldom has to be removed. Naiad says this makes their shaft seals last a long time, since most damage to the seals comes from sliding the shaft in and out. When the fin is removed, the shaft should be protected with a sleeve, as this one is.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Capt. Carl Gwinn

A low-aspect fin (wide but not too deep) is required on this big yacht to minimize draft; otherwise the fin would project beneath the keel. High-aspect fins (narrow and deep) are more efficient, because of their longer leading edge, but not always practical.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Naiad

This Naiad fin is pressed onto its splined shaft, and stays put without fastenings.

Removing it requires special equipment, though.

Note the narrow winglet at the tip of the fin to make it more efficient.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Naiad

It takes a skilled forklift operator to slide this Naiad fin onto its slightly tapered shaft smoothly, and without binding. Note the spiral groove in the shaft to help lock the fin in place. The white fitting in front of the shaft is a weed guard that has yet to be painted.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

Photo Credit: Naiad

Here’s another view of the Naiad fin being installed.

Note the size of the fin relative to the ladder; you know that fin is heavy, too!

The bottom of the winglet needs a couple of coats of antifouling before launch.

Read “How to Maintain Your Stabilizers”

The surprising thing is, for such a mechanically complex system, stabilizers are remarkably reliable, and more so if you maintain them correctly. Proper maintenance doesn’t come cheap, especially if it requires special tech experts and fancy tools, but it’s less costly to maintain systems than to repair them. Besides, do you want to be crawling around a hot engine room 500 miles offshore trying to corral a disabled stabilizer, or cleaning up hydraulic oil sprayed from a hose pushed beyond its natural lifespan? To keep things on an even keel next season, give your stabilizers a little TLC now.

Paravanes—The Stabilizer Option

This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Power & Motoryacht magazine.

Mike Smith

- More: stabilizer